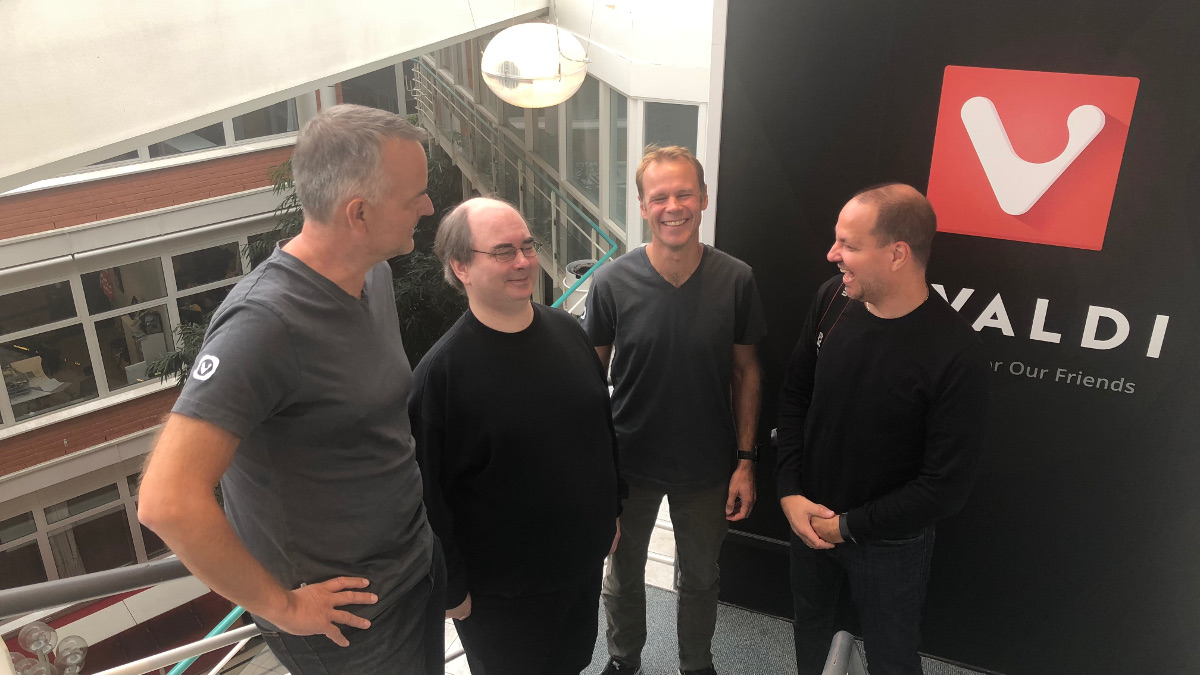

Last week, we had a visitor at Vivaldi HQ in Oslo. Both calm and curious, he was driven by the three C’s – code, Chromium and the challenges they bring along.

Harald Brombach from Norway’s leading tech publication Digi.no chatted with three of our developers – Yngve Pettersen, Jarle Antonsen, and Andre Schultz on the process of how Vivaldi is built upon the Chromium code – its advantages, challenges and much more.

We’ve often been asked how this process works, and we can’t think of anyone better than our developers to explain it. This insightful conversation deserved to be shared with you, and we are thankful to Digi.com for allowing us to publish the highlights of the interview in English. Read on.

Are the extensive code and high pace of development a challenge?

A new version of the Chromium code comes every six weeks, and it has to be integrated with Vivaldi’s own code. This is done by Yngve Pettersen, whose main responsibility is to maintain the code base of Vivaldi.

“It’s quite big and this job can take several weeks,” says Yngve.

Has the process evolved?

Earlier it took three to four weeks, but with the last two versions of Chromium (68 and 69), Vivaldi developers have managed to do this job in less than two weeks.

“We spend quite a lot of time on fixing code that worked with the previous Chromium version, but has stopped working,” shoots Project Manager Jarle Antonsen who works largely at a level above the Chromium Code Base, including the installation software.

How is the collaboration with the Chromium community?

“They are surprisingly helpful. I sometimes get stuck and many times have sent questions to module owners who come back with suggestions and make things easy,” says André Schultz, Vivaldi developer working primarily with the user interface.

Are there any contributions to the Chromium code by Vivaldi?

For the past six months, the Vivaldi team has submitted about a dozen patches to the Chromium code. This has primarily been about cleaning, such as removing the incorrect use of CRLFs (the Windows line endings) in source files that should only have LFs, but also some error fixes.

Yngve says he plans to send several other things upstream, but it can require weeks of preparation.

Recently, the team released Vivaldi’s extensions of the Chromium’s project generator tool GN on Github, which Vivaldi uses to specify how the browser application should be built. Here is a blog post about GN and the extensions written by Yngve Pettersen.

How extensive is this process?

“When a Chromium update arrives, I start working on a separate branch,” says Yngve. As I retrieve the code from Chromium, I sync all the sub-modules we use and make a few small changes there.”

“This part of the process has been made fairly automatic. Then, we take our own updates and copy them on top of the Chromium Code Base. This is a process that can be quite manual at times because we get a number of so-called ‘merge conflicts’. These can be problematic, but we have cleared up a lot of the code that causes these, so it has become much easier,” explains Yngve.

“Of the 900 files we’ve changed, there were about 80 files that had to be fixed. It took me five to six hours, a process that used to take up to a week earlier,” says Pettersen.

Once this has been completed, the code has to be compiled.

“It varies how long this task takes, but usually it takes a day or so to get the Windows version working. Linux, Mac and the other platforms can take some hours to build but are usually unproblematic. Overall, this process usually takes two to three days,” says Yngve.

How are new issues detected?

During the same process, changes have been made to the Chromium code that cause Vivaldi’s own patches to be rewritten. This can at times be time-consuming.

“After this Andre, Jarle, and other developers begin to fix the already discovered problems, as well as new issues that are discovered during testing,” says Yngve.

Is this process demanding?

According to Andre, Chromium is most demanding when making architectural changes.

“This happened a couple of times, where we have turned off a feature flag and worked in parallel next to Chromium, on a feature that is actually dying. It created a lot of work,” he says.

He mentions one case that was introduced in Chromium 64, while it is only now that Vivaldi developers have got it fixed.

Once these problems have been corrected, the work continues for a while until the team has a version that is stable enough to go out as a finished product.

“Then we create a new branch of this and just make fixes to finish stabilizing it before we release it as a finished version,” says Yngve.

What about the new functionality?

As developers add new functionality, the main code is continuously rebuilt and tested.

“Every time a new commit is added, a new build is created. These builds are extensively tested. When it comes to a ‘final release’, it is the QA that has the final say,” adds Yngve.

According to Yngve, there are around 20 developers at Vivaldi. He does not exactly know how many are working with Chromium at Google, but of course, it is far more. To give a picture of the difference in scale, he compares the number of commits the two teams have made recently.

“We have made a total of 17,000 commits to our main code since 2013, that is, in five years. During the past year, we made about 2700 commits. In comparison, between Chromium 67 and 68 there were between 11,000 and 12,000 commits. There were 15,000 between version 68 and 69 branch points. In ten days, they have made the same number of commits that we made in a year,” he says.

He adds that based on these figures, the Chromium team can be estimated to be about 600 developers.

“Usually it takes a very short time from an idea until we have the functionality to test. We do not have much bureaucracy for this,” says Jarle. He says that the CEO, Jon von Tetzchner, himself is very involved in both the testing and providing feedback.”

“New functionality depends a lot on what our users request. Their feedback is crucial,” concludes Jarle.

We hope that this blog has helped you get an overview of how the code integration at Vivaldi works. And we can’t thank Harald enough for coming over and getting our developers to talk about this complex process in a simple way.

Did you find it interesting? Too complex? Or? Let us know in the comments.

If you’d like to read the full story (in Norwegian), you can read it right here (paywalled) on digi.no.