People using the synchronization functions in Vivaldi (and other browsers) want to be able to do so with the knowledge that their data will remain safe from prying eyes. The standard way of ensuring that your data remains yours and yours alone is to use some form of end-to-end encryption scheme, which is what Vivaldi, as well as many other browsers, do. This ensures that the data stored on the Sync servers cannot be accessed in any way because it cannot be decrypted without the encryption key. However, there must be no doubt for the user that their encryption key is kept secret.

In this article, I will compare the ways several browsers handle the user-facing portion of data-encryption. In an attempt to explain why Vivaldi’s encryption key is handled the way it is, I’d like to look at the usability aspect as well as some of the most obvious pitfalls for inexperienced users.

How data encryption is handled in other browsers

Since Vivaldi is based on Chromium, it makes sense to start by talking about Chrome, since Chromium is primarily tailored for Chrome itself. Unfortunately, if you are using Chrome Sync, its default behavior is intentionally to not set up any encryption at all, except for passwords. Fortunately, Chrome (and therefore Chromium) does provide the option to encrypt all synced data, but that option is only available by specifically looking at the synchronization settings, which isn’t required during the set-up phase.

This is clearly easy to use but has the obvious pitfall that many people will never even realize that they need to manually set up encryption. As such, most Chrome users who use the functionality are probably sharing all their data with Google.

In contrast, I’ll next look at the way Firefox handles encryption for its synchronization function. They recently published a post which explains it in detail.

Firefox’s take on the encryption password is a cunning one (as expected, for a fox 😉). They use a single password that is then used to derive two unrelated keys: one for signing in and one for encryption. That gives them the guarantee to always have a different login and encryption keys, even though the user must only have one password. It’s an approach that works well for them and is easy to use but wouldn’t work well for Vivaldi.

The biggest risk I see is that the registration steps for Firefox Sync look pretty much like a standard registration page and do not make any mention that the password is used for anything particularly sensitive. Therefore, inexperienced users may decide to reuse a password that is already used for another service, which means they have effectively leaked their encryption key.

I want to mention Brave as well (which is also mentioned in the article I linked to above). Their approach is, in short, to use a separate encryption password which is forced to a long random string. This means the user must find some way of copying this string to any device where they wish to use the synchronization function of Brave. This more or less guarantees that the key won’t be leaked voluntarily, but it is not ideal from a usability perspective, especially since users may accidentally leak their key while trying to copy it around.

How are Vivaldi’s Sync encryption keys handled?

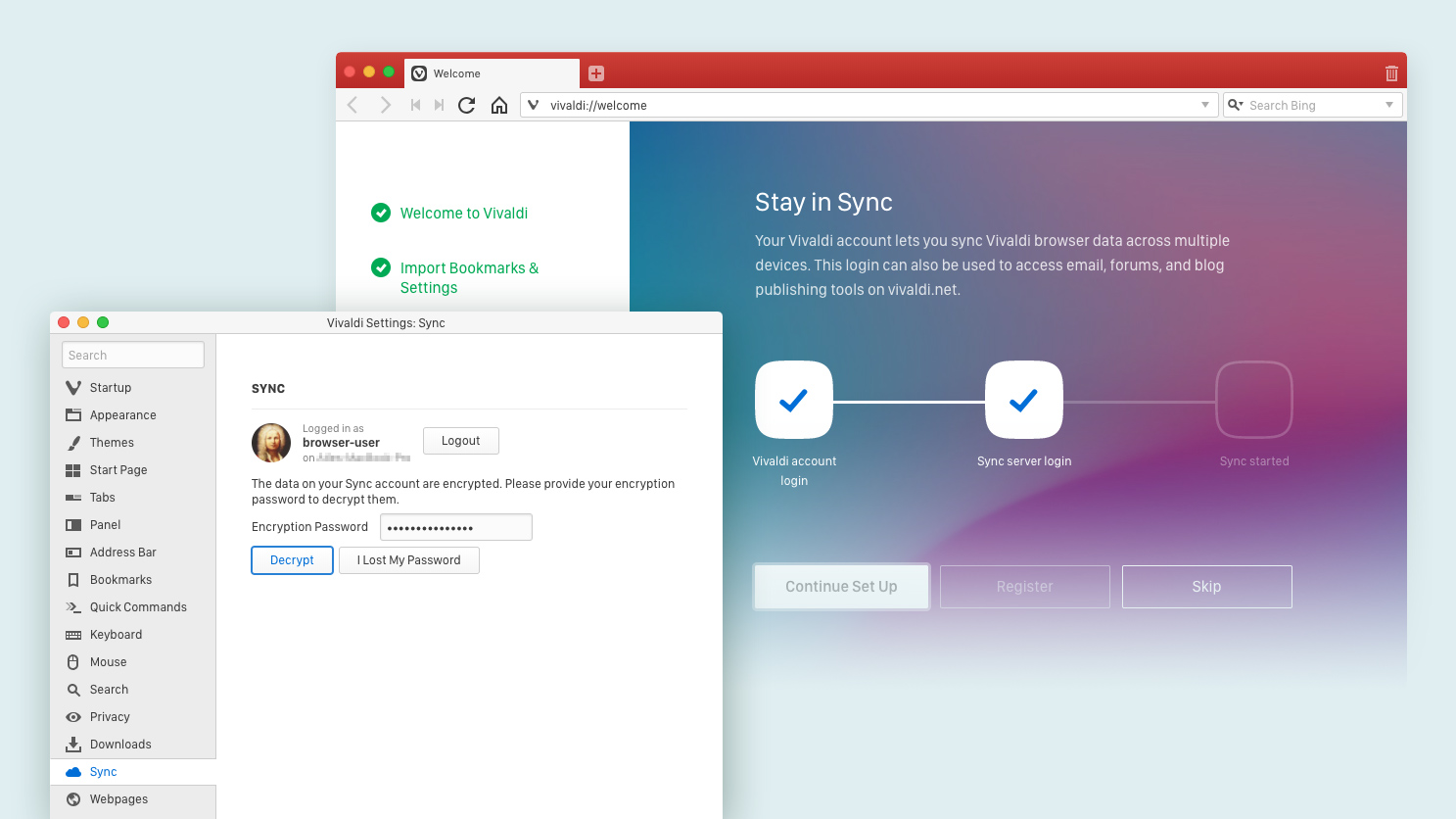

Vivaldi is based on Chromium, which means it inherits the encryption mechanism of the Chromium Sync-engine, which takes its own, separate encryption password. It does not, however, suffer from the same user interface weakness as Chrome which eschews encryption by default.

The Vivaldi Sync settings user interface will insist on being provided with a separate encryption password before starting the synchronization and tries to inform the user as to why it is needed.

Vivaldi’s Sync service depends on having a Vivaldi Account on Vivaldi.net. Since these accounts are used for other services we provide and have been around since well before we started providing Sync, we cannot easily use a key derivation mechanism like Firefox’s as it would require all existing users to change their login password.

As such, the password handling of Vivaldi Sync may not come across as being as user friendly as the two options above, but it does make sure that the user is made aware of the importance of choosing an encryption password (even though it is impossible to let someone choose a password and make sure they’re not reusing a previous one).

Vivaldi protects your data

In conclusion, the security considerations for something as basic as handling an encryption key are not trivial and there are some serious trade-offs to consider when it comes to choosing one method over the other. I believe that Vivaldi handles this challenge well, with a user interface clearly stating that Sync encryption protects their data in addition to the Vivaldi.net account login.

Ultimately though, the most important part is that you trust the company that provides the encryption functionality to behave honestly and not try to steal your key. You are trusting their software after all. I can only vouch for Vivaldi in that regard, but I am fairly sure the others mentioned here are also trustworthy. But if for some reason, you are using Chrome Sync, do yourself a favor and turn on encryption.