Read this article in 日本語.

The World Wide Web is 30 years old. I feel fortunate to have been there almost from the beginning. This is my story.

In 1992 I was working as an intern at Televerkets Forskningsinstitutt (TF), the research department of the Norwegian state-owned telecommunications company (Telenor). At the same time as writing my master thesis, I was fortunate enough to be part of a group working on this kind of technology.

We had just finished a project on Open Document Architecture (ODA), a document standard intended to compete with closed solutions, such as the Microsoft Word document format. We had made a word processor for ODA, which included an x.400 mailer and the capability to embed audio and video in the documents. Sadly ODA never took off, so our word processor never got much use, but the exercise was still useful, as we gained competence that we used when we made our first Web browser, Opera.

Working on the World Wide Web

After shelving our ODA project, we started looking for other interesting projects and we came across the World Wide Web. This is very early days for the Web. We quickly made the first Norwegian web page, which became the entry page for all other Norwegian websites. We then started to develop various technologies for the Web:

- We made a simple set of pages for use internally in Televerket. I remember a discussion on whether we could make use of images on the page at all, as they would make it heavy. I finally was allowed to use small images, 300 bytes each, to make the pages a little more interesting.

- We made tools to convert Text TV to Web content. There was not a lot of content on the Web at this time and this was a way to bring content there.

- We made a simple search tool that allowed you to search for terms (both positive and negative terms, to allow you to get as accurate results as possible) from various sources and display the results through a web page, email or fax.

- We made tools for converting documents to Web format. As FrameMaker was widely used in the research department, I spent a lot of time making a tool called Fm2HTML that ended up being used by NASA, MIT, and various other research institutes and companies. It was a lot of fun to be making a tool so widely used. Fm2HTML would take a complex document, including multiple files, references, images, and tables and convert it all to a set of Web pages.

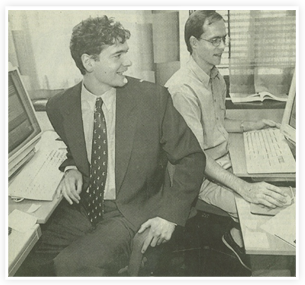

Geir, who later co-founded Opera with me, took a quick look at my Fm2HTML code and made it readable and structured. It taught me a major lesson. I thought I was good at coding, but Geir was just a lot better than me. I also tweaked similar, but more limited tools for Word Perfect and Word.

In 1994, we made the decision to make a browser, Opera, initially inside TF, but later we got the rights to Opera and were allowed to start on our journey on our own.

So since 1994, with a short pause between the summer of 2011 and the fall of 2013, I have been working on building Web browsers. The goal has been to get everyone on the Web and adapt the Web to the needs of the user. First at Opera and now at Vivaldi.

Grasping the potential of the World Wide Web

What the Web offered was unique in many ways and had the potential for a transformation of the world. Most did not see that, however, in those early days.

One of the benefits of the Web was the ability to adapt to the needs of the user. In the early days of the Web, the content and the formatting was not mingled. What this meant was that a lot of decision power was left to the browser with regards to how to show the content. This was a significant change and something we embraced, while others fought.

I remember being at a conference where this was discussed and there were people threatening with lawsuits if the presentation of a page was not 100% like they intended, which would have been really impossible as different screens had different fonts, but also because there was a lot of flexibility in the browsers in that one could select fonts and font sizes to display any content. We embraced this opportunity to truly adapt to the needs of the users, giving full control as to fonts, font sizes, zoom levels, colors and more to the users.

In the early days, there was also not a good understanding of what the Web had to offer. I remember having a meeting with members of the association for blind people in Norway. They were wanting the telephone catalog in braille. I tried to convince them that getting the telephone catalog onto the Web and providing braille from the browser would be more useful. I failed. I was unable to explain to them well enough the potential of the Web and they did not understand it.

Starting work on Opera

The decision to make Opera was not taken lightly. It came after months of deliberation. Our team was divided. Many in the team did not believe that we could compete. Partly because they had this view that we could not make software in Norway and partly because they believed we could not compete with the Americans (read NCSA Mosaic). Finally, seeing how slowly Mosaic was moving, we were given the go-ahead and started working on Opera.

From day one, it was our focus to adapt to the needs of the user.

My father is a professor in Psychology and has worked a lot with children with various disabilities and as a kid, I was quickly educated in the need to adapt to the needs of those that need it the most. Thus from the very beginning of Opera, we would make sure that fonts could be changed, colors could be changed and content could be zoomed. We also made sure that you could access content with keyboard shortcuts, including single key keyboard shortcuts, to make the browser accessible to as many as possible.

This vision was something that led us also to ensure that Opera would run on limited hardware, so that as many people as possible could get onto the Web, even on slow computers. This, in turn, enabled us to make Opera available on mobile phones, TVs and various other devices. To make the Internet available to as many as possible, we even ran Opera on servers and provided a small client, Opera Mini. The effective Opera code allowed us to do this.

Vivaldi is born

After I left Opera, the company threw away all our hard work and all our code. The positive side to that, however, is Vivaldi. As Opera turned its back to the principle of adapting to the users’ needs and threw away all the code, there was a need for a new champion of adaptable software and thus we have Vivaldi.

At Vivaldi we continue to work to adapt to the needs of users – everyone deserves a browser that fits their needs.

We continue to work for an open Internet and continue to build the Vivaldi browser and associated services.

The Web is 30 years old and has become very important. We need to make sure the Web continues to be open and free and that the privacy of its citizens is honored.