Read this article in 日本語.

Normally, a connection between your browser and a website passes from your browser to your computer, from your computer to your WiFi or home network (if you have one), from your home network to your Internet Service Provider (ISP), from your ISP to your country’s national Internet operators, from your country’s national Internet operators to the website’s country’s national Internet operators, from the website’s country’s national Internet operators to the website’s hosting provider, from the website’s hosting provider to the website.

That is a lot of steps! In fact, the traffic can even pass through other countries on the way, depending on where in the world you and the website are located.

No pretense of privacy on insecure connections

With an insecure connection, anyone who controls or shares any part of that connection, can see the data that was sent over the connection – whether it’s someone else on your computer, network, your ISP, the operators of the various sections of the Internet along the way, your government and the governments of any countries along the way, the hosting provider, or anyone else who owns a website on the same host.

It’s all visible.

Data sent over secure connections

When a website offers a secure connection (HTTPS URLs with valid certificates and high-grade encryption), and you make use of it, the data sent over the connection can only be seen by your browser and the website.

Wait, is it that simple?

Not really. In order to make the connection, the browser has to look up the website’s IP address using a DNS service, usually provided by your ISP. It then uses that IP address to make the connection. This means that anyone monitoring the connection will see the website’s domain being sent out in a DNS request, and can, therefore, work out what website you are connecting to, even if they cannot see what is being sent.

Even if you are able to use a secure DNS service, when the browser connects to the website anyone monitoring the connection can see which IP address is being connected to, and can use a reverse DNS lookup to work out what website you are visiting.

Enter VPNs

When people use a VPN for browsing, it is normally because they want to do one of two very different things:

- Hide their network communication from other users of their local network, their ISP, or an oppressive authority.

- Hide their IP address from the website, for privacy reasons, or just to access a website which blocks access to connections from certain countries.

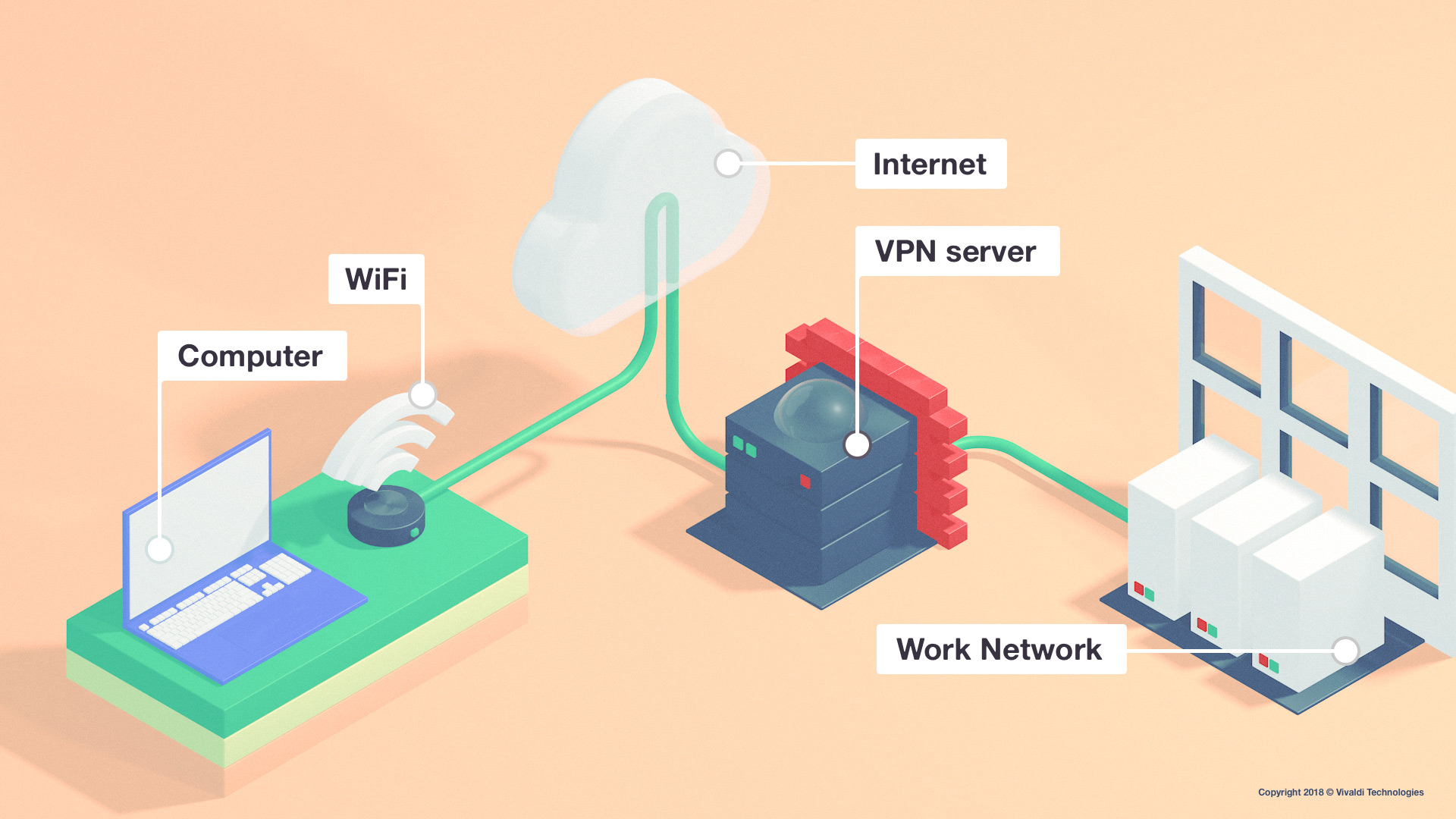

In their purest form, VPNs offer a way to securely connect your computer to another network, such as your employer’s work network. When your computer tries to send data over the network, a VPN service on your computer encrypts the data, sends it over via the Internet to the destination VPN server, which sits on the network you want to connect to. It decrypts the network traffic and sends it over the destination network as if your computer had done it itself. The responses from the network are sent back to your computer in the same way.

Anyone monitoring any other part of the connection along the way cannot see what was sent, or which computer on the destination network your computer was connecting to.

Sounds good but is this what most VPN services actually do? The answer is “no.” This is where proxies come in.

Proxy services explained

A proxy is a service that makes requests to websites on behalf of your computer. The browser is set up to connect via the proxy. When the browser starts to load a website, it connects to the proxy in the same basic way that it would connect to a website, and makes its request. The proxy then makes the request to the website on behalf of the browser, and when the website responds, it sends the response back to the browser.

This may appear to offer the privacy benefit of not allowing the website to see your IP address (appealing to the second group of users), but a regular proxy will, in fact, send your IP address to the website using the X-Forwarded-For header. After all, the proxy owners would not want to be blamed if you were to try to attack the website – this way, the website owners will know it was actually an attack coming from your IP address.

Of course, you could also try to add a fake X-Forwarded-For header to your requests to try to pin the blame on someone else, but websites can use a list of known and trusted proxy addresses to determine if your X-Forwarded-For header is likely to be fake.

Most proxies, known as HTTPS proxies, can also pass secure connections directly to the website unmodified since they cannot decrypt them without the website’s certificates. This allows HTTPS websites to be used through a proxy.

A proxy may also try to decrypt the connection, but to do so, it must present a fake certificate – its own root certificate – to the browser, which the browser will recognize as untrusted, and show an error message in order to protect you from the interception. This is sometimes used for debugging websites, and when doing so, the person who is testing will need to accept the proxy’s certificate. It is also sometimes done by antivirus products so that they can scan the connection.

Secure web proxies

Secure web proxies allow the connection to be made to the proxy securely, even if the website being connected to is using an HTTP (or insecure HTTPS) connection. This has the privacy benefit of preventing other users of your local network from seeing the network data (appealing to the first group of users). They can see that you are connecting to a secure web proxy (though the connection really just looks like a secure website connection), but they cannot see what data is being sent over that connection. Of course, the website can still see the X-Forwarded-For header, so it will still know your IP address (undesirable for the second group of users).

To be trustworthy, a secure web proxy also uses certificates to prove its identity, so you can know that you are connecting to the right secure web proxy – otherwise, someone could intercept your proxy connection, and present a fake secure web proxy, so that they could monitor your connection to it.

Anonymising proxies

An anonymizing proxy is basically just a proxy or secure web proxy that does not send the X-Forwarded-For header when connecting to websites. This means that the website cannot see your IP address, making you anonymous to the website (appealing to the second group of users).

Some services also offer the option of intercepting the page to remove JavaScript and other unwanted content, but this means that you also must supply the proxy owner with any logins, and the proxy owner is able to see what you are doing, even on secure websites. It just swaps one privacy risk for another privacy risk.

It would appear that an anonymizing secure web proxy would solve both cases at once, but it is not that simple, and there are many other things to consider, e.g. how your network and computer are set up. Your computer may also send out DNS requests when you connect to a website, CRL and OCSP requests when using website certificates (if CRLSet is not available), and the browser may also send out other requests, such as malware protection blacklist requests, or thumbnail requests. This is where a VPN can be better (but it is important to note that most are not).

It also means that if a user uses the proxy to launch an attack, the proxy service will get the blame. To avoid this, the proxy owners may throttle connections, or require logins, and keep logs of connections, so that the correct person can be held accountable. This defeats the purpose for anyone trying to use the proxy for privacy.

What to look out for in a VPN service

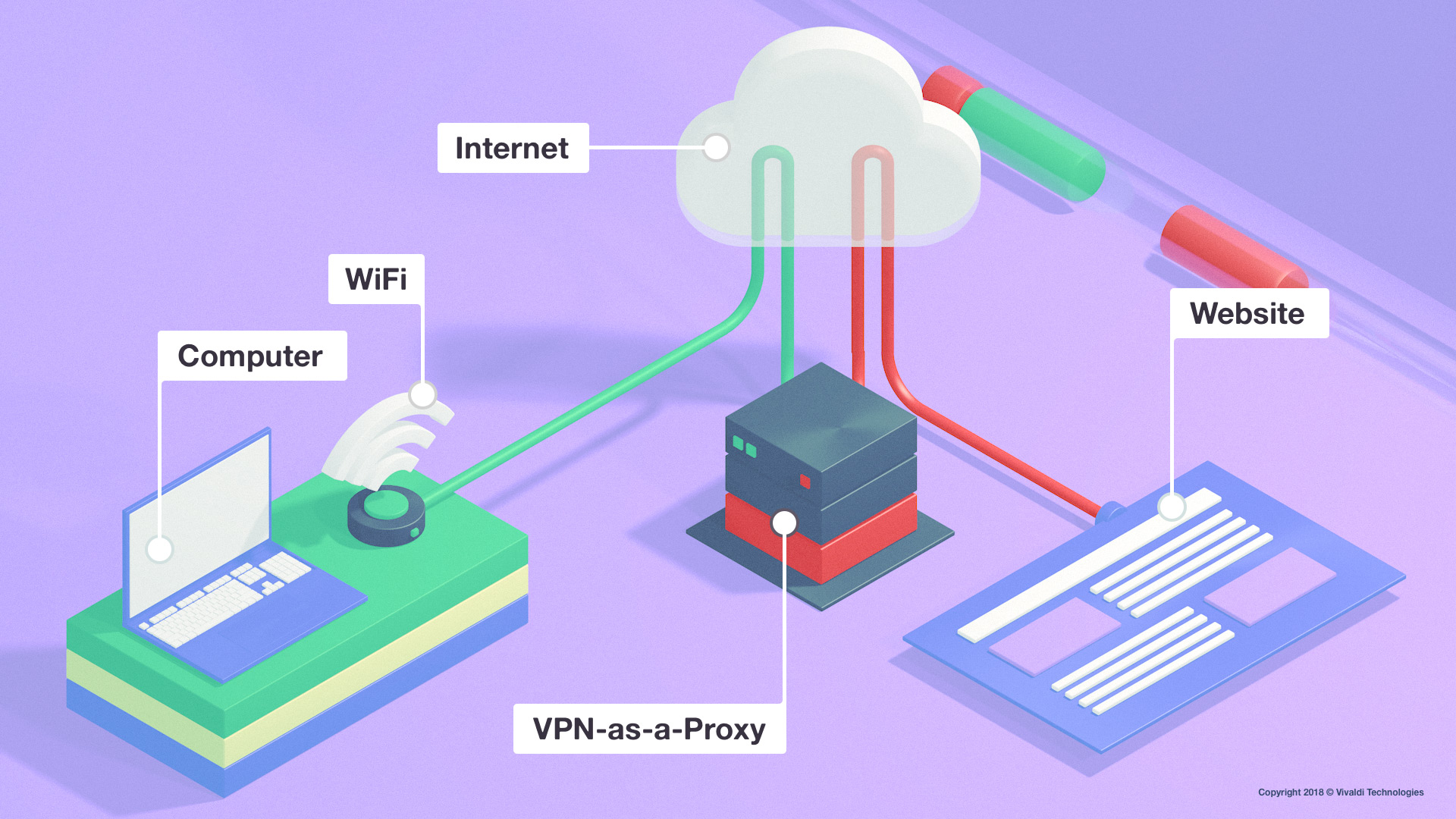

In most cases, VPN services are nothing more than an anonymizing secure web proxy labeled as “VPN”. They often claim that they “secure website connections” or “encrypt your website connections”. Neither of these are true but many companies resort to phrases like these to keep up with the competition. A VPN service of this kind cannot possibly secure a connection to a website, because it only controls part of that connection.

In other words, the VPN is not being used as a pure VPN, it is being used as a proxy. While the connection passes securely between your browser and the VPN server, it then has to leave the VPN server’s network and return to the Internet in order to connect to the website. The website connection is just as insecure (or secure if it uses HTTPS) as it’s always been. The connection could still be intercepted during the second half of its journey. All the VPN can do in this case, is to add a little privacy over part of the connection.

In addition, secure (HTTPS) connections are about a lot more than just encryption. They also provide assurances that the connection goes to a website that owns a trusted certificate which proves that nobody has intercepted the connection and presented a fake copy of the website. A VPN cannot alter that, and it cannot turn an insecure connection into a secure connection. Without the certificate handling, even a completely encrypted connection is not secure.

Enhancing privacy

When talking about VPNs, we desperately need to move away from using “secure” and start talking about enhancing privacy, because that is what a secure web proxy or VPN-as-a-proxy actually does.

In theory, a VPN-as-a-proxy would not need to be anonymizing, but in practice they almost all are.

The biggest difference between a secure web proxy and a VPN-as-a-proxy is that the VPN – when using a proper VPN service on the computer – can capture all relevant traffic, not just the traffic initiated by the browser. A VPN can also capture the DNS, OCSP, CRL, and any other stray traffic generated by the browser which may not relate to the website connection itself (such as malware protection checks). In some cases, the browser may be able to reduce the amount of these when using a secure web proxy, such as making its own DNS requests, but there are still cases which cannot be reliably captured on all systems. Therefore a VPN-as-a-proxy is better than a secure web proxy which is pretending to be a VPN.

Browser VPNs

If a browser application offers a feature, or an extension, that claims to be a VPN that works just for that single application, it is a good sign that it is not actually a VPN but an anonymizing secure web proxy. This doesn’t make it bad, it just means that it’s likely to have limitations that prevent it from capturing all traffic related to the connection. It may not capture DNS traffic (but in some cases, it can, depending on the implementation). It may not capture certificate revocation checks made by the system. This means that although it may hide the majority of the traffic, it might still allow little bits of information to get past the proxy, and someone who is monitoring the network traffic from your computer might still be able to work out what websites you are visiting – an important privacy consideration if you belong to the first group of users.

A VPN-as-a-proxy is much better in this case as it captures all traffic from the computer. This does mean that you would not have the same choice; either all traffic from all applications goes through the VPN, or nothing does. You cannot just have the traffic from a single application go through the VPN.

However, both an anonymizing VPN-as-a-proxy and an anonymizing secure web proxy can be quite effective at hiding your IP address from the website, so the second group of users can be well covered.

Other tips

- Disable any plug-ins which might reveal your IP address via other means.

- In Vivaldi, disable broadcasting of your local IP address with WebRTC (Settings – Privacy – WebRTC IP Handling – Broadcast IP for Best WebRTC Performance).

- Use a clean profile or private browsing mode, to remove any existing cookies or cached files that can be used for identification.

Stay tuned for more tips in our series on privacy and security.

* * *

Read more blog posts from the series:

- The basics of web browser security: an introduction

- Shared networks, tracking and fingerprinting

- Your browser, antivirus and other network intercepting software

- Website permissions and third-party services in Vivaldi

Main photo by Hannah Wei on Unsplash.