Join Bruce Lawson and Vivaldi Browser CEO Jón von Tetzchner as they review the top tech stories of 2024! In this episode, they discuss the landmark Google monopoly ruling, the shifting dynamics of the browser market, and their thoughts on the Apple Vision Pro. They also explore the future of Chromium, rate each topic as “brat” (good) or “næt” (not so good), and share insights on the challenges of building and maintaining a browser engine.

Transcript

[Bruce:] Hello again, everybody. Welcome to the fifth edition of the For a Better Web podcast. In this podcast, I, Bruce Lawson, Technical Communications Officer for Valaldi Browser, talk to somebody who in their own way, in their own industry, in their own manner, are working to make the web a better place. And as we hurtle towards yet another end of year, I find that my thoughts turn to the events in the tech industry over the last 12 months. And who better to discuss them with me than a venerable stalwart of the tech industry and the browser industry himself. He looks young, but he isn’t quite as young as he appears. My very own CEO, Jón von Tetzchner. Hello, Jón.

[Jón:] Hi, Bruce.

[Bruce:] How are you today, sir?

[Jón:] Doing well. How are you?

[Bruce:] Not too bad. It’s not yet snowing here in the United Kingdom. We reserve that for January and February. So, yes, it’s not too bad. Thank you.

So, yes, Jón has been making a list. He’s been checking it twice. He’ll no doubt tell us who’s been naughty or nice in the tech industry. But, of course, we’ve been informed by our annoying Gen Z or “Gen Zee” intern, Bendix cx, that we can’t use the terms naughty or nice anymore because they are “OK boomer”. We have to use the term “brat” or “næt”. And for those who don’t know what “brat” means, and I have to say I didn’t, it’s a way that young people express approval of something.

So, depending upon when your formative years were, you might very well have said “sick”, “bad”, “wicked”, “cool” or “groovy”. Certainly when I was young, we used to say, “Verily it doth please me, by my troth.” This is what I would say every time Mrs Lawson and I had been to see the opening night of one of Mr Shakespeare’s new comedies.

So, Jón, I don’t know if you just want to practice saying brat in a convincing Gen Z way.

[Jón:] Can I do that even?

[Bruce:] Try it.

[Jón:] Brat or næt? Does that sound…

[Bruce:] Yep, that sounds great. Brat is an exclamation of approval. næt is its Norwegian negative. (Folks, it isn’t really. We just needed something that rhymed with brat, that wasn’t swearing.)

Google vs DOJ court case

Okay, so, for the very first thing, these are in no particular chronological order. Recently, the United States courts have ruled that Google is a monopoly in search engines, and the Department of Justice, who bought the case, have been vindicated. They’ve been asked what they suggest Google’s remedies should be. There’s a whole lot of them on the table, including selling off or breaking off of Chrome from the search engines. So, before you give a definitive one-word ruling, what were your initial thoughts on this case, Jón? Do you think Google was a monopoly, is a monopoly?

[Jón:] Does anyone think they’re not?

[Bruce:] Google don’t.

[Jón:] Well, I think this is a complicated matter, and in some ways it isn’t necessarily always a question of being one monopoly or another. I think the world has changed in some ways. In the old days, we were kind of talking, okay, there’s a monopoly. But in a way, what we have now, we actually have a handful of companies that rule the internet in many ways, and all the rest of us, we live there. And Google is definitely one of them. There’s a couple of others that I would mention naturally in our case, which is Microsoft and Apple. And those are the ones in which world we live. And I think what we have, which is not great, is that when you have a competitor and the competitor owns the platform you run on, and products that you compete with at the same time. And this is rather special, and obviously with the markets here that a company like Google has, yeah, there is a problem there. So what does it mean? I mean, if you look at Google search per se on a worldwide basis, I mean, they have like 90% market share. That’s pretty significant. And it kind of has an implication for everyone that’s on those platforms.

[Bruce:] If they have a 90% market share, though, does that indicate monopolist practices, or does that just suggest that they are the best at search?

[Jón:] It doesn’t need to mean anything from that perspective. I mean, you can have a significant market share. It doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re doing things that are bad. But obviously, I do think there is clearly a case where Google is well aware of their positions and that there is a problem there with the connections between both operating systems, search engines, browsers and other services. So, yeah, I would say Google is definitely practicing being a monopoly there in this game, like our other competitors as well.

[Bruce:] Of course, because there’s Google search, there’s YouTube, which is basically synonymous with online video or certainly online hosted video. Chrome, which was heavily pushed by Google properties and for a while on the Google search page. But it’s complicated somewhat by the fact that there’s Chromium, which is the open source project that Chrome is based on and which Vivaldi is also based, which Opera and Brave, DuckDuckGo, et cetera, are also based. So, do you see that whereas the courts were correct in calling Google a monopoly, do you see a danger with the potential split off of Chrome or Chromium for the ecosystem?

[Jón:] I think there’s always a question what’s going to happen in a situation like that. But if they were to be split off, I mean, I would presume that the company that would then be Chrome Inc (or something like that) would have an interest in keeping Chromium alive. What’s the point of buying it if you don’t keep at it? And secondly, I would think that all the other companies that are making use of Chromium have an interest in keeping it going as well. Is there a possibility that something strange would happen, that someone would say, OK, I just want to go in my own direction and I don’t want to be part of an open source project? I think that’s a risk with open source project at any one time. Anyone can decide to do that. There is no “OK, you will stay on the straight and narrow for any time”. So does it change the risks? I’m not sure. I think there’s a lot of questions. You can also discuss: Is this the best remedy? Are there other remedies that are better? I don’t know. I think this is actually really, really complicated because it depends on how different parties play their cards. And again, the special thing in our industry is that there isn’t one monopoly. Again, you have Google as a monopoly, you have Microsoft as a monopoly, you have Apple as a monopoly and you have others that might want to get in on this game that are maybe slightly on the outside of what we are doing, like Facebook. So we have to keep all of that in mind that there is a dynamic in all of this. But I still think it’s really important that you have regulators and that they try to keep a level playing field, which when it comes down to it, is what creates innovation and the like. If it’s really hard for smaller companies to come into those markets and make a difference, then you have a problem. So, I mean, we have to see where all this goes.

[Bruce:] I completely agree with you there. The DOJ case that they’ve started against Apple, which hasn’t as far as I know even gone to court yet. The DOJ explicitly makes the case that Apple’s behavior now would prevent a new Apple-like organization being able to establish itself in the market. So it’s almost as if these big companies that started off in the early halcyon days/ wild west days of the internet are pulling the ladder up after them. And of course, I suppose it’s not only other browsers that make heavy use of Chromium. I guess Adobe have significant interest in Chromium. Bloomberg, the financial services industry or organization, all of their terminals are based upon Chromium. It would seem to me that it wouldn’t only be up to small browser manufacturers to perpetuate Chromium, but they could actually be a sort of industry conglomerate or consortium of interested parties who fund it. But I don’t know. Are you volunteering to lead that, Jan?

[Jón:] No, I think I’ll leave it to someone else. I just like to focus on building our browser. And now, obviously, I do have the experience of building a browser core from the beginning, or at least working with a team that did that. So when people are talking about, hey, why don’t you do this or why don’t you do that? I mean, people will say something like, why don’t you build your own core? And I’ll try to explain to them, OK, when I quit Opera, we had 100 people that were working on Presto. So 100 people to maintain. And I was making the argument at the time that we should increase that group of people probably by 10% per year to be competitive. And that was maintaining a well-written, well-organized, beautiful piece of code.

But again, there was a decision made by the management after I left to kill Presto. And some people seem to think that I could have basically just taken that code. But that was not an option. And in many ways, it was one, it wasn’t mine anymore. Secondly, having 100 people working on the core and then more is not feasible. So I think if you look at it over time, I mean, Opera was one of the few browser companies that actually made a browser from scratch. Hardly anyone else did. They started with something.

I mean, if you go all the way back, most of the browsers have actually some, they go back to Mosaic in some ways. Well, Mosaic became Netscape kind of, I mean, and onwards from there, Internet Explorer was initially a license of the Mosaic code. There is other elements like this. I mean, a lot of the current browsers came out of KHTML, which then became WebKit, which became Chromium. So WebKit and Chromium are kind of related. And when you think about it, so Apple, they had built a browser before. But when they started again, they didn’t start from scratch. They started from the KHTML code base. They then built a browser there and then Google took that code base and built on that forward.

So there’s a lot of history with this. Microsoft obviously moved over then to the Chromium code base. So did Opera. And in a way, when we were then starting with our browser, we didn’t really feel that there was a natural order choice. That is kind of like we could have gone with the Gecko code base with a fairly limited user base. And at the time, going through fairly significant rewrites, or we could go where everyone else was going. So this is complicated.

I mean, a lot of people are talking about wouldn’t it be great if we had much more choice when it comes to browser engines? I would agree with that, that it would be good. But I think realistically at this time, doing that just requires a lot of work. And again, trying to explain a lot of this because this is complicated. You would say, hey, well, I mean, why don’t you? I mean, you can spend time doing that. But I think realizing that a lot of the time spent when you build a browser engine is compatibility and potentially malicious compatibility issues. Again, over the years, we’ve had issues with our competitors having important sites that block our access to services. We even had that issue with using Chromium. So we had to change our identity when visiting sites.

OK, I’m kind of rambling here because I’m not sure there’s a point with all of this except, yes, I’ve built a browser engine or I work with people that do. Really smart people, this is not trivial to do to start from scratch, which is why I think what people are finding is that it’s better that we work together on a code base and it’s actually better for everyone. Is it possible that someone would say, I don’t care, I just want to go by myself? It’s possible, but there’s a significant risk in doing that because part of the issue is there will be security issues found in that other code base that you’re working from. How are you going to deal with that as the code deviates over time? I think that’s in a way a massive, massive potential problem.

If you have totally different code bases, quite often you’ll find that there are similarities in issues and the like. But when it comes to security issues, you don’t want to linger. You want to have fixes out really, really quickly. And if you then have, there’s a security issue that’s fixed in a competitor, and by the way, I do think people in general, they collaborate when there’s a security issue. People are generally wanting to work together because what you don’t want is to have a security issue in the world and no one actually having control over it. Because overall people are wanting to work together on this. But if you have similar code bases with security issues, how are you going to ensure that a security on one doesn’t happen on another? And again, in worst case scenario, the code base has changed so much that actually this is going to be non-trivial to fix. There’s a number of issues with this. So, all of this is quite complicated. And so the question is, I think anyone that would want to go solo in this would have to deal with that kind of issue potentially.

[Bruce:] So, would it be fair to characterize your opinion that saying that Chromium is too big to fail, and too big that none of the bigger interested parties have a vested interest in allowing it to fail? It would survive and continue even if hived off?

[Jón:] Well, I think, again, I mean, definitely the company, if there is a company that’s going out, if there’s a Chrome Inc, it would be kind of absurd if they wouldn’t see the value in Chromium. So, I would definitely think that they would be interested in keeping that going. And similarly, anyone else that’s in the ecosystem that is using Chromium would have the same interest. I just have a problem seeing that Chromium wouldn’t continue one way or another through the interested parties of which there will be many.

[Bruce:] So, in one word, brat or næt for the DOJ finding Google to be a monopolist?

[Jón:] Brat.

Browser Choice Alliance

[Bruce:] Nice. Talking of monopolies, you’ve mentioned one, Google, of the big three monopolies. Let’s talk Microsoft because this year saw the launch of the Browser Choice Alliance, which is, and I’ll confess an interest here, folks, because I was one of the people who led Vivaldi into this. It’s an informal alliance between some smaller browser vendors, and Google Chrome as an equal member, to persuade regulators worldwide, starting in the EU because their process is further down the line, to persuade them to regulate Microsoft Edge, the browser on Microsoft Windows. So, Jón, so I don’t get bored of hearing my own voice, could you briefly explain why Microsoft Edge should be regulated when it seems like it’s less than 10% of the market share of browsers?

[Jón:] I think, I mean, when it comes down to it, basically when you start with Windows, which continues to be the most used desktop operating system, you then need to download another browser. And a lot of people do. At the same time, Microsoft will do everything they can to keep you on their browser. And part of that is utilizing that browser when you’re then trying to download another browser and similarly search engines and the like. So all of this is kind of interrelated from that perspective.

I think if you try to look at companies like Microsoft, they have a long, long history of trying to utilize when they have a power in one market in another one. They’ve done that, I mean, as long as I can remember. And I remember the old Netscape case all the way back in the early days of the internet when their goal was to kill Netscape. So this is where all of this starts. And I think what’s happened, yes, Microsoft has lost some markets here, which is in some ways incredible in the browser operating, in the browser market.

But they are still a very significant player. They’re still where we have to go through to be accessible. And the point is, they’re really making it hard for you to select another browser and I mean, all kinds of self-preferencing going on. So what does this mean in practice? I mean, one thing is OK, which browser is included with Windows? It’s Edge. You want to download another browser. There are potential warnings against that on the way to doing so. You want to set it as default. It’s definitely a lot harder than it is with other browsers. I mean, you have to go through some hoops.

Now, in the case of Edge, Edge will be set as default through one update, through a bug, through a multitude of different ways. Suddenly just Edge will be default. And then what does it mean to be default? Does default mean that you click a certain file and it will open in that browser? Yes. But it may also mean other files. And this is where it becomes interesting when Microsoft maybe selects some files and then you click another file that an alternative browser could have handled. And for some reason, it starts Edge and the next thing is Edge is back to being default.

The search function in the Windows, does that go to the default browser or does it go to Edge? Well, it goes to Edge. What about potential other applications that Microsoft may be having built? There’s also that case where they ignore whatever is the default browser and they go to Edge instead. There’s also the question, if you install your browser, is it going to be visible on the operating system? And the answer to that question by default, it probably wouldn’t. There’s just so many hindrances that make it difficult. You have to convince people to download your product. Obviously, if you’re from a small player, I mean, those kind of warnings might actually have an impact that they’re saying you can’t be there.

So I think with the history and what we’re talking about here, we’re talking about large companies with a lot of power that have a tendency for self-preference and it’s kind of in their genes. And I think saying you can do bad stuff in this case, but not in that case. I don’t think it works. I think you basically have to say you cannot self-preference in those cases where it’s meaningful. And that includes also any services that you provide. I mean, if you’re providing a service, if you think about it, if there isn’t anything, if you’re just saying, OK, I have a service, I would like to be available to as many users as possible. Then you have a natural way of building products. You say, OK, I have this service. I would like it to work with every other browser out there. Makes sense, right? If you’re making decisions to go against that, you’re probably doing something bad. And I think this is the kind of thing that we’ve dealt with over the years as first at Opera and now at Vivaldi.

I really think, I mean, part of this is because there’s been more focus on Google and Apple and the monopolies that they have. And then people are saying, well, Microsoft has been losing ground. But the reality is they haven’t lost that much ground. And the reality is they’re still a really strong player. And for a company like ours, for example, Windows is the most important platform. And so it really matters what Microsoft does that and any hindrances or limitations in our products being used on the platform is a massive issue. And so I really think they need to be regulated. I think the companies that are in those special positions, and we’re not talking about a lot of companies, it’s basically a handful and for us, it’s basically three, they need to play fairly. And again, then the results for users. I mean, always when there is competition, you’ll end up with better products, better services, at better prices one way or another.

[Bruce:] So your argument is that regulators should look at an organization as a whole rather than specific products on it, because like with Google, where they have their fingers in many different pies across the ecosystem, they can do things in one unregulated product to what nudge people towards a regulated product. And it’s an ever shifting landscape. I think that’s why Microsoft haven’t been, attention hasn’t been so much on Microsoft is that their tactics change. They move things around or they move nudges around between products and in different territories and randomize it too. So, I mean, that’s why I urged us to join the Browser Choice Alliance simply because it’s important, I think, to make the markets and the regulators aware of what’s happening on desktop. Because naturally people think about mobiles because it’s sexier, but desktops are still where millions, billions of people are. So Browser Choice Alliance, brat or næt?

[Jón:] Brat.

Apple Vision Pro

[Bruce:] Hey, hey, that’s two so far. OK, let’s get the third monopolist out of the way. This year saw the release of the Apple Vision Pro. I haven’t used on myself. A few years ago, I bought my son an Oculus Rift headset thing for Christmas and I tried it and I felt incredibly nauseous. Whether or not that was too many glasses of sherry and too many mince pies could have been a contributing factor, but it didn’t work for me. But a lot of people are excited by it. Are you?

[Jón:] I find it interesting. And like, I mean, my son is really into VR and that like, and I can see the fun with the technology. But I guess it’s not where I mean, I like the real world. If you saw that kind of the Iceland Verge ad that Iceland made to kind of make fun of Zuckerberg’s alternative reality. I kind of like the real world better. That being said, I do think it’s an interesting technology. I think it can be used for a lot of cool stuff, both for games and being able to go places. I think it has a lot of promise in many ways. But on the other hand, I’m kind of excited about the real world and just living in it from that perspective.

[Bruce:] Same. I wonder whether this is a generational thing because, you know, neither of us are going to see 30 again. Perhaps not even 40. And our sons love these devices. So perhaps is it a generational thing or is it, could it be that it’s not generational, but it’s to do with the fact that young’uns have more time for leisure? I don’t know. Is it a leisure technology?

[Jón:] I think currently it primarily is a leisure technology. I mean, there have been uses which are kind of for other things, but I think it’s mostly used for playing games. And I think it can give a fun experience to me. It’s kind of it’s interesting. And I think that’s kind of what we’ve been seeing, that it gains a lot of traction and a lot of a lot of hype. And then it kind of dies down a little bit. And it’s done that kind of many times because this kind of technology in many ways isn’t new. It was there at the early days of the web in many ways. Obviously it’s gotten a lot better over the years. And I think, again, some people really like it for games. And OK, that’s obviously fine. I do think it’s probably one of those things you don’t want to overdo. I think there’s discussions on the consequences of overdoing gameplay inside those systems. It’s kind of playing with your senses. So I don’t think there’s been maybe enough research on kind of the overall consequences of that. Obviously, some of the things that you talked about feeling nauseous, I think that also depends on the quality of the systems. But obviously you are kind of messing with your brain and our brain is really good at adapting in general. But sometimes our brain will just say, hey, hey, hey, I’m moving in a certain way. And what I’m seeing is not in relation to that. And that’s making me dizzy. And so I’m sure they’ll work on things like that. And I’m sure they’ll find devices that are more compact with less extra systems that they need to have around you. So it looks like you’re in some weird science fiction thing. But overall, I think it’s an interesting technology to play with. I’m sure there will be positive use of the technology as well. But a world where we would live in those? Not so exciting for me.

[Bruce:] No, no, I agree. I mean, for me, I can see the appeal of gaming, although I don’t get time to do it myself. And I’m aware that gaming is an industry that now apparently earns more revenue than Hollywood and the music industry combined. There’s a lot of money.

[Bruce:] No, I was going to say it occurs to me as well that a lot of the younger generation, certainly in the United Kingdom, where I am, they game heavily, manipulating their senses with these things. But there’s been a lot of lamentation amongst the hospitality trade that young people don’t drink very much alcohol anymore. And I wonder whether they are just substituting voluntary sense manipulation that we did, maybe with beer and wine, with their VR headsets to the same effect.

[Jón:] I don’t know about that. But I do think, I mean, gaming has changed. I guess I’m still kind of preferring the older games that we had, kind of just sitting down with a space invader or Galaga or something like that, a little shoot them up, do that for a few minutes or an hour and then be done with it and not letting anyone down while doing that. I think there’s been a fair amount of research going into how to keep people engaged in those systems, and I think it can go too far. And obviously part of I am concerned about kind of payment systems and the like where you’re paying. And obviously, I know the gamers don’t like that either, where you kind of you can pay to advance in a game. I think a lot of people don’t like that, but obviously overall games have advanced massively. On the other hand, I still think the gameplay of something like a space invader and Galaga is fantastic, and I will just stick with those for a while.

[Bruce:] Yeah. I was a big fan of Asteroids, the original line drawing black and white thing. I legendarily spent an hour, one school lunch break getting 89,000 points. But yeah, actually it never occurred to me what you’re saying. So when it was put 10 pence into a slot to play a game, the machine obviously had a vested interest in kicking you off pretty quickly. So it would get the next 10 pence from the next punter, but now when people spend a lot of money on a console that they own, there presumably isn’t the same impetus to finish the game quickly to get the next punter on. The game manufacturers want to suck you in and keep you there forever. So gosh, yes, it’s all about the engagement once again.

Okay, so Apple Vision Pro, brat or næt?

[Jón:] Næt.

[Bruce:] Oh, we have our first næt, very interesting. I think in part of it, and just explaining a little, I think it’s an interesting technology. I think it’s far too expensive and not kind of game changing enough to warrant the price. So I think, I mean, is it interesting? If I was just looking at the technology, I think it’s interesting and I think it’s good that there’s new players coming in with alternatives. But am I personally excited about it? Not really. To me, to be honest, it always seems like a solution in search of a problem. The technology is fascinating just as a technology, as a science, as an exercise of miniaturization and sensor development. But because I’m not a gamer, I just don’t see its value to my life, which allows me neatly to segue into the next solution in search of a problem that may or may not be too expensive.

“AI” and Large Language Models (LLMs)

And of course, we’ve seen, again, huge advances in inverted commas. So I’m giving my opinion away, sorry. In AI, artificial intelligence, obviously, which is a bit of a catch-all terminology. And regular readers or regulars to the world of Vivaldi will know that we organizationally have a take on AI, which is that we’re not building it into any of our products. Has anything happened this year to change your opinion of AI, LLMs? Is there a difference that we need to draw?

[Jón:] I don’t think very much has changed. I mean, I’m not and I think we are not really saying that AI can’t be useful for any things. And I mean, in certain things, we’ve seen improvements that are positive. We’ve seen positive improvements in translations and voice recognitions and the like. And I think you could potentially use this pattern recognition technology with research in the medical field and the like, where you can utilize it to find facts based on the information that recognizing patterns. I think it is a powerful feature that you can use for a lot of things. On the other hand, the way it’s been used mostly is to create crap. Sometimes, I mean, it’s kind of like, OK, it’s impressive at times. Oh, we can write this fantastic text. And it’s just basing it on everything that everyone else is writing and it’s finding the most natural way to put words together and the like. And the problem is, how is this actually then being used?

And I mean, it’s taking up massive power. And at a time when we probably should be trying to find ways to reduce power usage or generate more power or the like. This is utilizing a lot of power. And what is it being used for? Spam mails. I mean, what has improved and called, I don’t know if it’s a great improvement, but the spam mails, we’re getting a lot more professional. They’re written in our own language at times. They are definitely a lot better than they used to be, which sadly means that more people may fall for them. We do look for search results and search results are very much more seemingly AI generated. Quite often the ones that come at the height of the lists. I do think with any system that is basically based on popularity, there is a significant possibility of misuse. And I think it’s a possibility to change facts by just if you get enough sites to repeat misinformation that can go into those systems as being the truth. And I mean, they’ve been struggling with that, but I think it’s an inherent part of the system. And then they try to put in ways to avoid that. But we are still getting those things. You ask if you get enough sites to say that two plus two are five, that might become the answer that comes out of those systems. And that’s a problem. I also think that looking for information and finding things has a value. So in particular, if you’re going to ask some some genie in the sky a question and it will get it wrong a lot of the time, that isn’t great. And I mean, it’s difficult enough to just get the right search results. And I mean, getting the top, the most relevant search results, even on the first page is hard enough. And you’re trying to get one? Yeah, I don’t know. I do see a fair amount of issues with the technology.

And I think in a lot of ways, there’s a significant risk that there’s then more data collection. And as a company, we do think there should be less data collection. We’ve kind of talked about that there should be regulation again with regards to what companies are allowed to collect of information and how they’re allowed to use that information that they happen to have on customers. Because a lot of tech companies naturally, by providing services, will have information about their customers. And I think it’s really important to not misuse that information that you have. And again, if that’s just going into one black box and being part of an AI system, I mean, Reddit being used for AI, who would think that’s a good idea?

[Bruce:] Yeah, yeah. I mean, I remember when my kids were little and of course, they grew up with the Internet. From the time they were sentient and able to do things by themselves, the Internet was there pretty much on demand. Remember them saying, I saw this on the Internet and I would say, remember that the Web is a communication medium. It’s not necessarily an information medium. If you saw some bullshit on the Internet, it’s still bullshit. And I find I’m having to sort of repeat that conversation now with people about AI. I saw it in the AI. Well, the AI is just predictive text, ultimately. It says something that sounds convincing, but it doesn’t have any knowledge of the world. And it concerns me.

[Jón:] And I think part of it is basically calling it what you’re calling it. I mean, what we are all calling it, we’re calling it AI. Is that the right term even? And in some ways it is more of a model that learns from input and finds kind of outputs based on that. And it isn’t necessarily the best output, depending on how the system is built. It’s more like what is the most likely output and most used output in that setting. And I think there’s a lot of issues with that in also many ways. And it’s interesting to see the discussions on this, how this is impacting us. But obviously, what we are seeing now is we are gradually seeing more and more AI results in search. It’s getting harder to find the information that you’re actually looking for, which is the source of the information. There is, again, posts. You go into something like Facebook, and I was kind of fascinated. Facebook actually has some settings to say I want to see less of this crap. There’s also to see more of it. I don’t know why you would want that. I want to see more kind of data that is not real, made by some machine. And I was even more misinformation, please. I mean, it’s a setting. I’m kind of thinking, what are they thinking about?

[Bruce:] Well, I don’t know. I’m just having an epistemological crisis now, because you’ve said all AI is is the ability to take input that you’re given and reconstruct it and output stuff. And you might very well be wrong. And I’m thinking, so am I. So is everybody.

[Jón:] Well, you can say that we can all make mistakes, but what we definitely don’t need is a system that basically we look at the DNA, that we ask for information and it gives us the wrong answers. And I think part of this is also, I don’t know about you. If I see it, I can look at a picture and I can think, oh, this is beautiful. Right. And if it’s Photoshop, so it’s fine. If it’s AI generated, come on. I just want to see if you want to impress me with your photos. Yes, you can do a little bit of filtering, but if it’s AI generated, it’s something else. And I feel kind of OK, I just wasted my time seeing something that’s automatically generated. So I think overall, it’s interesting because AI is supposed to save us a lot of time. I think at this time is actually wasting a lot of time because, again, we’re spending more time on kind of incorrect information. I was reading about the Python guys kind of dealing with error reports that were basically AI generated and were then wrong. And that’s a significant problem with these systems. If you’re sending people that are potentially doing voluntary work, basically reports that are generated by some machine and you haven’t even bothered to ensure that that report is actually correct. Then you end up with a significant problem and a lot of time wasting. And again, this idea that we send an email to someone, we get the system to make it for us. And then on the other end, there’s a system that takes a summary of that. So why don’t we just send a single line of text then? At least it will get the communication going instead of, OK, we have a system that takes one line of text that makes it into a page. And on the other hand, you have a thing that takes the page and made it into one line of text. And then the question is, are you ending up with the same line of text on both sides? And most likely you’re not. So there’s a lot of room for problems with this. And I understand that people will argue, hey, this is saving us time. But I think a lot of the automatic systems that we are dealing with are not working really well. And a lot of people don’t like having to deal with automatic systems. And it isn’t a question of whether the automatic system. Recognizes you in a better way. I mean, dealing with things like I mean, this is just bots and the like. I mean, so you’ve been trying to do something on a Web page and this is typical at times. You’re doing something on a Web page. There’s an issue. And then it will say, call this number. You call that number and you talk to a machine on the other end. And you’re I mean, if I wasn’t be able to deal with that machine when I was talking to it through the keyboard. Is it going to be a lot better when it’s actually struggling with my accent or I mean, quite a lot more limited? So there’s there’s issues with this. I think a lot of companies are thinking, OK, they can save money by putting in technologies like this. But and I think that I’m not saying it’s black and white. I think there’s definitely cases where you can make this work usually with a more limited data set. We’re looking at specific things, but the generic ones are pretty broken at this time.

[Bruce:] Well, because Gen Z, sorry, Gen Z likes black and white. I’m going to pin you down to an answer. AI in 2024. Brat or næt?

[Jón:] Næt.

Social Web/ Fediverse

[Bruce:] I wholeheartedly concur and not just because you pay my salary. So a marginally more cheerful question now. 2024 for various reasons has seen a lot of people leaving Mr Musk’s marvelous fascism machine, erstwhile Twitter. And a lot of people have gone to the Fediverse or probably to Mastodon. But there are other instances of the Fediverse out there that people can go to. I’m imagining you see this in the same way that I do, which is this is encouraging. Also, a lot of people are going to Blue Sky, which claims it’s federated. I haven’t looked at the tech deep enough yet. I’m a Mastodon man myself because I’ve been bitten once by investing in a social network, investing my time in a social network that’s owned by an individual. What’s your take on Blue Sky, Mastodon, Threads, et cetera?

[Jón:] Overall, I mean, what I’m excited about is the Fediverse. That’s what I love. I mean, to me, it’s just reminding me of the early days of the Internet where we were fighting with big companies like this, whether it’s AOL or CompuServe or something, which had their closed systems. And I think that’s where the Web starts. We have to remember this is where the Web starts and anyone can set up a server with information and a lot of companies and people would do that. And then you would put up some servers where people would put their content on. There’s a lot of details to this. But to me, the Fediverse is in many ways the same way. I mean, there’s thousands of different Fediverse servers. I mean, we have one with Vivaldi Social. There’s a lot of Mastodon-based servers, but there’s also based on other Fediverse technology, whether you want to have something that’s a video service or something more like a blogging platform or the like. There’s a lot of different services that you can connect with. And there’s an open platform underneath and that platform is written by the W3C. So to me, that’s OK. It’s doing all the things right. It’s not a standard so-called that is owned by a company. I don’t consider anything to be a standard if it’s owned by a singular company and there’s no one else contributing. If it’s there’s a standard, there’s a group of people working on the standards which represent different companies and different interests and they work on this together. And then there is different implementations of that. And that’s the power of what we are seeing with the Fediverse.

[Bruce:] Certainly, there feels like a renaissance of excitement in the air about it. I’m very aware that I’m talking with other people who are invested in Mastodon on Mastodon and so I’m in a bit of a filter bubble. But certainly the kind of people who seem to have kicked off the early Web, probably before I got on the Web in the year 2000, seem to have moved to the Fediverse and the same sort of spirit of openness, hacking for good, hacking something that is designed to work together rather than designed to silo, seems back. Or maybe that’s just because I’m projecting my own wishes onto it. I don’t know. But something’s in the air.

[Jón:] There’s a lot of positives there and I think there’s a lot of, and again, I mean, the beauty of it, you can make your own server. You can make it for a certain group of people, but at the same time, you can have access to everything that’s on the other servers. But you can also decide that you want, OK, I don’t want to connect to that server because I don’t like how they deal with content on that one. So you have choices like that. You have a lot of flexibility. I also just like the fact that what you see in your feed by default, like on Mastodon, you’re seeing the content from people that you’re following. You’re not seeing, there’s no algorithm saying, OK, I want to see kind of whatever that machine thinks you want to see, which tends to put us all down there with some kind of rabbit hole. But instead, you’re just seeing the people that you’re choosing to follow. And you can search for people and you can hear different voices and the like. And I think it has a lot of positivity in that respect. And it links with other things like RSS, it links with all the services. I mean, a lot of sites have RSS feeds coming from them as well. So you can follow that inside the same system. There’s just a lot of power potential there and it’s early days. And I think we all have to work on building this because I think this is a much better building blocks than what we have in the older systems. I think the older systems are just as good as the dictator or whoever is in charge. And you can hope it’s a good one, but then there’s a change and then it isn’t anymore. And a lot of the systems over time, we’ve seen that again and again and again. There’s this, OK, we start with a nice business model. And then at some stage we change. And I don’t think that’s a great situation with these kind of services. And I think at times I’ve been digging up this article from Tim Berners-Lee, which is more than 10 years old, where you talk about social media companies and silos that are being built and the problems with those. And the Fediverse is the opposite of that. And again, we’ve seen the damage that these kind of systems that try to keep you inside the system, to try to keep you engaged and the consequence of algorithmic content, which basically pushes potentially hate speech. And the like, it tends to do that. I mean, hate speech kind of engages us and misinformation seems to engage us as well. And obviously, potential interest in amplifying that kind of content from some parties. There’s a lot of complexity here, and I think it’s better to go for the simple solutions of basically seeing chronological content from people that you follow and being able to interlink with any server out there. And then you can choose to make your own server. I really think a lot of companies and schools and governments should be making servers themselves. And through that, then you know who’s behind that information. And there isn’t just some party that can decide, OK, I want to block this. And you will still have access to that information unless, again, your server chooses to block that content, in which case you can switch to another one and take your data with you.

[Bruce:]For me, it’s the openness, the federatedness (if that’s a word) is almost of secondary importance, because to me, it’s the lack of algorithmic content that’s the killer USP, if you like. I’m sick of being manipulated. I’m sick of being enraged to be engaged. I’m sick of my hatred of hate speech being actually turned into somebody else’s profits. You say it’s early days for the Fediverse, but of course Vivaldi Social hit its second birthday last month or something. So Vivaldi got on board very early before I joined. What was the impetus for that?

[Jón:] I mean, we were just seeing this as what it is, that we are seeing this as the start of the continuation of the web. And it’s basically the web fighting back against the silos in some ways. Now, obviously, the silos can decide to connect with things. And there’s a lot of discussions about that, that you have things like threads connecting. But I still think it’s a positive thing that you have an underlying technology. You just choose the servers you want to be on. I think actually in some ways, at least for me personally, I can follow a couple of people that are on threads. That’s fine. It’s just like being on another server, but I can choose the server that I want to engage in the most. But this is about fighting for an open web. I think this is part of that. And for us, that’s very natural. It’s a very natural thing to be supporting technology that’s utilizing W3C standards that is distributed. And obviously, I also love the fact that, like you said, the data is chronological and not using some algorithm to decide what you’re seeing. I think there’s a lot of value in this. I think it’s really important to support it. I think the current systems, they are proving themselves to create more problems than any joy that they’re giving at this time. So we need to get as many people to move over to the Fediverse as possible. And then we have to keep it on the straight and narrow ourselves.

[Bruce:] So to a one word adjudication: the Renaissance of the Fediverse in 2024, brat or næt?

[Jón:] Brat.

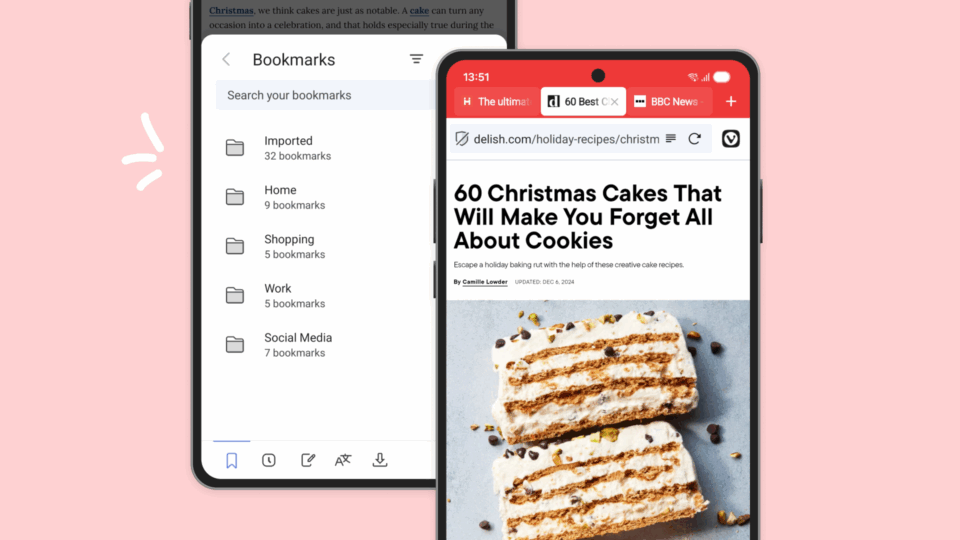

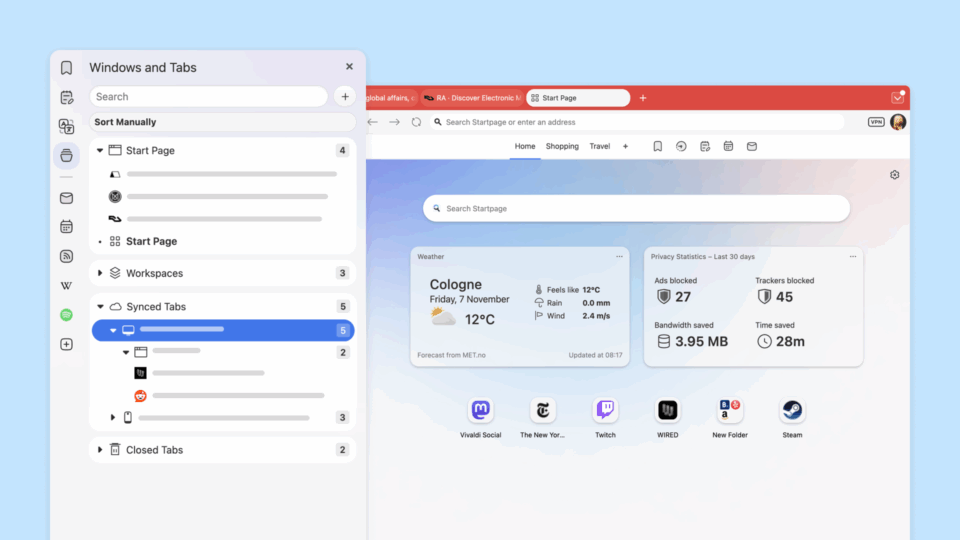

Vivaldi 7

[Bruce:] I thought you would say that and I wholeheartedly concur. Something else that happened in 2024 was, of course, a major release of Vivaldi, Vivaldi 7. I’m not going to ask you whether you think that’s brat or not, because obviously you do. But do you want to talk us through the main things that were in the 7 release and the reasoning or the thinking behind them, how they came about? Because I don’t know that people know, you know, did you just sit there on a throne and say, make this happen? Or how do these features get developed? How does it get into the product?

[Jón:] I mean, the thing is, we’re a company where ideas can come from anyone, right? This isn’t some, this isn’t like an apple with Steve Jobs, the way they would talk about it in the past, that you would have someone at the head that would just say, OK, this is what we do. People have ideas and we implement them. And people inside the company have ideas. People outside of the company have ideas. We work really closely with our community. But obviously what we are thinking about with this release, I think a lot of focus was on the dashboard. I think that’s a really unique feature that people will see more of moving forward because it’s early days. I mean, there’s a visual update that a lot of people are excited about. And we are kind of always adding levels of the features that you just don’t find in any other browser. We’ve been doing that for a long time. And in this case, we decided to focus quite heavily on the front page. And what we’ve done there is that, OK, if you’re using Vivaldi for things like mail and calendaring feeds and the like, you can include that in the dashboard. And you can include kind of Web widgets as part of this as well. So you can make a dashboard with the things that you would like to follow. And it’s up to date and quite powerful. And I think we built a building block. And what we’re going to do from now on is to build more services. And at the same time, you can build them yourselves on the server side and the like. So it’s a really, really powerful tool, obviously, in addition to the other tools that we are having. But we are kind of finding a lot of excitement from our users that, hey, I can do something special now. And how you use it is a little bit up to you. I mean, do you want to make, you can make a really nice looking feed reader out of this as an example, if that’s your focus. And again, this is in line with our thinking where you follow content and you don’t have an algorithmic system that decides content for you. You say, OK, I want to follow the BBC. I want to get by it. I want to get this. I want to get that. And I want to see that in that display and get an easy overview over it. And I think that it’s a powerful new tool, similarly for email and calendar. And again, any kind of service that you might put in there, because when you have a WebView, you can put anything. Anything that’s on the Web, which is basically anything.

[Bruce:] So presumably in a dashboard widget, Web widget, you’re getting the responsive mobile. Yes. Yeah. So it’s just a Web page, but tiled up on your dashboard with your feeds, with your mail, with your calendar widget, whatever you want.

[Jón:] Basically.

[Bruce:] Nice. What’s coming next? Can you tell us? What can we expect in Vivaldi 8?

[Jón:] You know, that’s going to be a little bit of time because we typically go through a number of releases. I mean, we will continue to evolve Vivaldi based on the feedback that we get from users. In some ways, this is something that we don’t necessarily know what’s going to be coming in a year. We make decisions on the way. We have a direction where our goal is to basically provide the tools that our users want, the flexibility that they want, the privacy levels that they want. And we want to build that into one tool to give them as much control as possible. And again, I mean, seeing that we are all different, we all have different opinions on how things should be. And there isn’t one answer to how things are supposed to be. This is kind of providing that flexibility. And we’ll do things. I mean, like we did things, we did a visual update. Right. And typically what we find out whenever we do a visual update, there are people that are going to love it. And there are people that are going to say, no, I don’t like that. But we always provide you with a way to get it your way, whatever that is. And that’s something we’ll continue to do. That whenever we do changes, we hope you like them, but we won’t get offended if you don’t. We’re not invested in you having to do things in a certain way. We acknowledge that you have whatever reasons you may have to prefer to do things in your way instead of ours. And there’s no saying that whatever we are doing is the better, which is why we provide multiple ways. And actually, my experience has been, I ask people even inside the office, how do you want to have things and you’ll get different answers. And it’s just natural. So for me, a lot of things about, I mean, I love using the keyboard. Some people are into using the keyboard. Some people are not. It’s fine. And I mean, the other functionality that we put, I mean, we put in a pause function of all things. Right. Thinking there’s too much internet, just pause it. Right. I mean, so we built a browser, we still put in a pause function. We think it’s the right thing. I mean, at times you just want to turn it off. Maybe it’s just because someone rang the bell and you need to go and check on that. And you want to stop that film from running. But hey, whatever it is.

[Bruce:] Right. So the pause function pauses everything in the browsers?

[Jón:] Kind of more or less. I mean, obviously the internet will continue moving. It’s not like that, but it will kind of, it will stop kind of operations on videos and the like. So it’s, so from that perspective, it kind of pauses everything.

[Bruce:] I’m assuming that if I ask you, Brat or næt, about Vivaldi 7, you’re going to choose the former option.

[Jón:] Of course, Brat.

Predictions for 2025

[Bruce:] Before we wrap up, what do you, what’s your prediction for 2025? What do you think we’re going to see in the tech industry? More AI, more Fedi, more weird monopolistic behaviour? Or are we going to see things steadying down a little bit?

[Jón:] I think we can expect to see a lot of everything. And I think where things go is kind of up to us. Right. I think there’s a direction where there’s more and more AI. And we have a choice. Do we want to follow in that direction or do we want to go in a different direction? And our feeling and our users feeling when we’ve been asking them is they don’t want us to go there. If they want to use AI services, they can do that themselves. They don’t want it built in because building it in typically means that we are profiling you to a greater extent. So I think that’s definitely a direction where things are going. There will be AI and then there might be a counter one. I think I’m hoping that more and more people will understand the problems with the algorithmic content and what it’s doing to our society. And that we need to work together to bring people over to the Fediverse. That that’s a goal for ourselves, for everyone. And that’s something that we will try to contribute to. And I hope that others will do the same.

And again, I mean, we are seeing things we haven’t even mentioned: crypto. And crypto is a disaster. And sadly, the way it’s looking now, crypto will continue to go upwards until it will not. And a lot of people will lose on this. And that’s a concern because it’s something that has no inherent value. I mean, you look at AI, we can discuss their pros and cons. With crypto, there’s just cons. There’s nothing there. I mean, with AI, I can say, hey, I actually like the translation. The translation services have gotten a lot better using this technology. But I can’t say that with crypto. It’s basically there’s a scam out there. And the valuation of those is just random. So I wish I could say that we’ll get rid of crypto in 2025 and we’ll say, OK, let’s save the planet instead, instead of wasting energy on useless stuff like that. But we have to see.

I think we all need to make choices. And the choices we make have implications. And hopefully a lot of us will be choosing, obviously all should be on Vivaldi. And that’s a good start. But but that we choose the Fediverse, that we try to influence all the people, because a lot of the people that are in the Fediverse are unique. And this is something that I’ve been seeing over time. I do my surveys and I ask a question, which browser are you using? And it is not the top browsers in use that are coming up on the list. The same with search engines where Bing got like one percent and Google six percent in my survey and smaller search engines were more liked. I think we all need to select kind of these different tools. We need to work on that. And I think we have the capability together to to make a difference and start in one corner and just work on it. So hopefully we can make 2025 a great year. We should definitely do our best to do so. Certainly in Vivaldi we will.

Bruce:] Jón, thank you very much for your time. I hope that you and yours have a brat 2025. And to listeners and viewers, wherever you are in the world, whatever you’re celebrating, or not, we wish you peace and joy in 2025.

[Jón:] Peace and joy.

Bruce:] Thank you very much. And we’ll see you next year.

Show notes

- Mr Shakespeare’s comedies

- Google vs DOJ court case

- United States v. Apple lawsuit

- Bloomberg terminals based on Chromium

- Presto rendering engine

- KHTML

- Vivaldi user agent changes

- Open source maintainers are drowning in junk bug reports written by AI

- Browser Choice Alliance

- vivaldi.social for free mastodon account

- Social Web Foundation launches, supported by Vivaldi

- A nice photo of a hedgehog