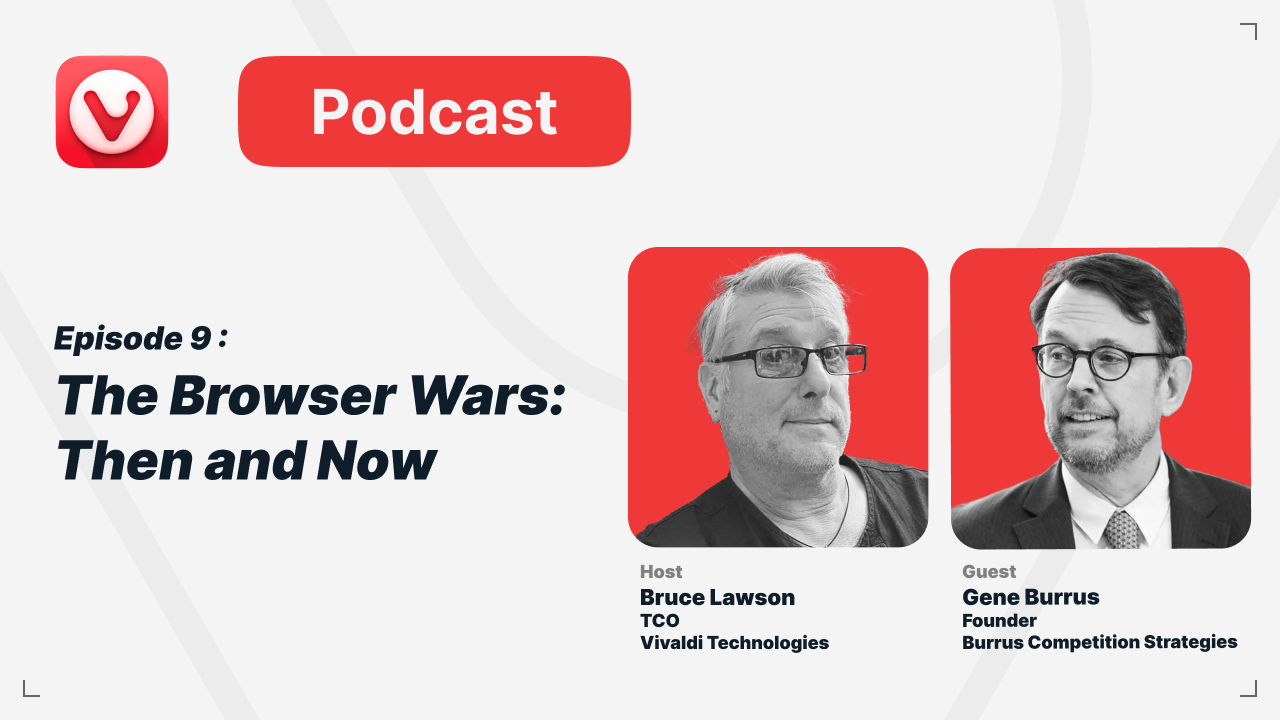

In this podcast series, Bruce interviews people from across different communities and industries who, in their own way, are fighting for a better web.

In this episode, Bruce chats with Gene Burrus, who formerly worked as Assistant General Counsel for Microsoft, working on legal compliance after the landmark Netscape anti-trust case, and now advises Vivaldi and others in the Browser Choice Alliance about how to stop Microsoft going back to its old ways. On the way, we discuss the Cold War, TV courtroom dramas, and why Gene prefers to be poacher-turned-gamekeeper.

Transcript

[Bruce:] Hello, everybody, and welcome again to another edition of the For a Better Web podcast, in which I, Bruce Lawson, Technical Communications Officer at Vivaldi Browser, talks to somebody who, in their own way, in their own industry, is working to making the web a better place. And this week, it’s my pleasure to introduce and welcome Mr Gene Burrus, all the way from sunny Seattle.

[Gene:] Hello, Bruce. Nice to see you.

[Bruce:] Now, full disclosure, everybody. Gene and I have a professional relationship. He is an advisor to the Browser Choice Alliance, which many of you will know was co-founded by Vivaldi, Chrome, Opera, and Wavebox, and has Midori just joined it. We don’t usually invite lawyers onto the show, primarily because I can’t afford their fees. But Gene, you have a very interesting history because you trained as an aeronautical engineer, I believe.

[Gene:] I did. I was an aeronautical engineer in my former life and worked actually building missiles during the Cold War a long, long time ago.

[Bruce:] Wow. And when the Cold War ended, I suppose you had to find yourself something else. So you became a lawyer.

[Gene:] Literally, my first job ended when the Soviets and the US signed the Intermediate Range Missile Treaty and my project was cancelled as a result. And members of the KGB actually got to come to my factory and inspect my desk.

[Bruce:] Wow. I hope your desk was suitably clean. But you soon swapped desks that vaguely smelled of uranium to a desk that vaguely smelled of sulfur, because you went to work at Microsoft where you worked on the compliance team, I believe.

[Gene:] I did. I joined Microsoft in 2002 as an antitrust lawyer. And if you remember back to 2002, that was right at the conclusion of the US DOJ and States’ case against Microsoft around browsers in particular. But, you know, middleware was the term of art back then. But it was the beginning of a long period of compliance efforts by Microsoft to obey that that court’s order. And then eventually similar cases were brought and resolved in Europe as well, at that time. So it was when Microsoft was probably the company under the most scrutiny in the world for antitrust problems. And so did that for a while at Microsoft.

I ended up spending 15 years at the company. First, working compliance and advice and counseling around those issues that were present in the cases. And then I took on the role of trying to apply those laws to Microsoft’s competitor with equal vigor, which is how I’ve come to do what I do today, is I got that experience not just defending, but also applying those laws to others.

[Bruce:] So given that, whereas you and I of course retain our youthful good looks, you’ve given away that you were working in the cold war, and I was at work at the same time as that. But many of our listeners will be perhaps even too young to have even been alive when the Netscape and Microsoft case happened. Would you mind just giving a brief overview to set the scene?

[Gene:] Yeah. So, you know, back in those days, there was, you know, the internet was new, if you can believe that. And people were just starting to figure out what could be done with it. And of course, at that time, most people in the world that were accessing the internet had to do so on a Microsoft Windows computer, because that made up 90 plus percent of all computers on people’s desktops back then. And a company called Netscape was the first browser company. They started their business. They were selling their browsers. That was back in the days when you would have to go to a store and buy your software in a box and plug in the disks, the floppy disks to load it on your computer. And Microsoft, after Netscape was starting to catch on, Microsoft introduced Internet Explorer, and started including it with Windows, and started doing other things, both with contracts with the computer manufacturers and technical interoperability issues, and were put on trial for that, for monopolization by the U.S. government a number of states.

And that was you know that was kind of the first case of the century in in tech back in the late 1990s, Microsoft lost that case it was ultimately … it was initially –and relevant to some current events– it was initially ordered that Microsoft would have to break up as a result of that antitrust finding. And ultimately the case was resolved with a consent decree order from the court, but that required certain conduct from Microsoft around interoperability requirements and the way to manage defaults and other things like that on the computer. And to some degree, the rest is history. For 10 years, they were subject to kind of constant oversight by the courts, by the Justice Department, and by what was called the Technical Committee back then, which was an independent group set up to advise the Justice Department on what was going on. They had access to Microsoft’s offices and source code, and everything back then. And that was that. So for a good decade, Microsoft was under a great deal of scrutiny and requirements concerning how their browser would work on the computer, how it would interact with third-party browsers, and how third-party browsers would be allowed to get on the computer and to access all of the resources in Windows.

[Bruce:] And you said that for a decade, Microsoft was under a great deal of scrutiny, and presumably therefore behaved itself. Was it was the court case resolved like you you must do this for 10 years and then after 10 years they could relax or…?

[Gene:] It was it was an order of actually the initial order was for five years it was extended by the court for another five plus and and and then at the conclusion the court’s jurisdiction kind of goes away and there isn’t, I would say the the impetus to focus the mind, so to speak, that a quarterly appearance before a federal judge who has the ability to find you in contempt of court might drive, with respect to conduct within the company. So since that time, it’s, they aren’t under the formal jurisdiction of the court. So their conduct is kind of ungoverned by that consent decree. It’s still governed by antitrust laws in the United States and elsewhere. But those laws are notoriously vague. And, you know, do they ever apply to anyone? It’s the case, I think, you know, even the Microsoft case was meant by the government, I think, to kind of define the contours of conduct by dominant tech platforms. It hasn’t really served that purpose, I think, as we’ve seen in the last few years, because the new dominant tech platforms have faced their own charges. They haven’t checked their conduct based on that finding. They argue why that case doesn’t really apply to them, either. And Microsoft probably today would argue why that case doesn’t apply to them in 2025 like it did in 1999.

[Bruce:] Because of course, we’ve seen, and the reason that you and I know each other and the Browser Choice Alliance was formed is because Microsoft is back to some of its old tricks with attempting to steer people away, scare them off, whatever, from installing other browsers on Windows. And it successfully argued that it doesn’t have to abide by the EU Digital Markets Act because Microsoft Edge doesn’t have a huge market share. Can you speak to that and why that is, why that might be arguable, and the arguments against that?

[Gene:] Yeah, they, you know, under the Digital Markets Act in Europe, which is an ex ante regulation of these digital platforms rather than waiting for a long investigation under Article 102 or Article 101 in Europe, or under the Sherman Act here in the United States. It is meant to govern that conduct going forward without having to go through that kind of litigation.

[Bruce:] Oh, that’s what ex ante means, is it?

[Gene:] Yes. Thanks. So, yeah. they’ve argued that because Edge’s market share is not particularly dominant in any realm, that they shouldn’t be subject to a lot of restrictions around it. However, Windows operating system still maintains a dominant share of desktop and laptop computers, PCs around the world. And it’s the way that Windows and Edge interact with one another and the requirements they put on that I think makes most of their conduct subject to the DMA, despite their arguments. They haven’t—you said they successfully argued they haven’t. They haven’t successfully actually argued that their conduct is compliant with the DMA, and I think we will see some decisions around that in the coming year, perhaps.

But it is the case that Windows continues to be on 75% of laptops and desktops, and Edge is on 100% of all of those computers because it comes with Windows and it interacts with Windows. And unfortunately, I think in ways that third party browsers simply can’t access, or equal, or take advantage of. And I think it’s the kind of conduct that would have drawn swift response from the DOJ, and the court, and the European Commission 20 years ago. They would have immediately called and expressed their displeasure, and Microsoft probably would have altered its conduct in the face of the threat of a judge finding them in contempt, or the European Commission finding them in violation. And so it is that they’ve had a period now of, I would say, either relief from the antitrust authorities, or the focus has turned elsewhere, and in some cases rightly so.

But it’s the case that they continue to have a strong position on desktop computers. Desktop remains relevant and important for many purposes. And they are engaging in conduct that probably would have drawn swift rebuke 20 years ago. It’s now a problem of kind of reintroducing the antitrust authorities to why it remains relevant and why it remains a problem. and why they should be just as swiftly rebuked this time around.

[Bruce:] For listeners who aren’t aware, some of the things that happen, so if you get a new Windows machine, the only browser on is Edge. If you open Edge to download another browser, the default search engine is Bing. In the case of Vivaldi, for whom I work, if you type in “download Vivaldi”, you’ll get a message sponsored by Microsoft in Microsoft Bing, the default search engine on Microsoft Edge, saying something like, “are you really sure you want to download another browser because you have Edge?”

They’d argue perhaps that because Microsoft Bing isn’t subject to the DMA and because Microsoft Edge isn’t subject to the DMA, That’s allowed. We dispute that, but that’s what they’re saying. But there’s other things as well, aren’t there, like more deeply intertwingled with the operating system. Any link to Microsoft Teams or any link in the operating system or the widgets are prefixed with a Microsoft Edge protocol rather than HTTP or HTTPS. which means they open in Microsoft Edge and nobody can change that. Is that correct?

[Gene:] That’s right. So it’s, you know, I liken it. It’s competition by frustrating users’ choices and expectations instead of kind of winning them over because they prefer Edge. It’s taking customers that have a clear preference for something else like Vivaldi. They’ve gone to the trouble of downloading Vivaldi, even though all the barriers are up in front of them. And yet, despite making this conscious choice, they are then presented with, I would say, unexpected behavior from their computer because they thought they were choosing Vivaldi as their browser. And instead, they get surprise launches of Edge that they neither wanted nor intended.

[Bruce:] So it’s actually, it’s just as much a consumer protection problem, isn’t it?

[Gene:] It’s very much a consumer issue. They have, you know, consumers should have choices and consumers are making choices. And then to a large degree, Microsoft is taking steps to thwart those choices, or to override those choices, which is bad for the consumers. It’s really, you know, from Microsoft’s perspective, it’s degrading the value. It’s because they have market power, that they can degrade the value of the Windows experience, and get away with it to some degree. It’s like, you know, they should want to respect their own customers’ choices too, but they obviously have decided there are reasons why they would rather frustrate their users to force their other products on them.

[Bruce:] Which allows me neatly to segue then to the next question and I’m very aware that i’m speaking to a lawyer so I i’m going to ask you to speculate. Why would Microsoft want to prevent third-party browsers running on Microsoft Windows?

[Gene:] It’s a good question it’s it it seems kind of gratuitous on its face a little bit. You know, why would they bother to do that? I think there’s a couple of things in play, and this is speculation at this point. But one, I think that desktops have become, after many many years, that mobile has been the place where commerce has been conducted on the internet for the last 10 years, you know. Suddenly desktops have become very relevant again in the context of artificial intelligence and how people are putting that to use. You know, people still primarily use their desktops for creative purposes, you know, writing, reading, consuming, but they do things on their laptops that mobile simply can’t substitute for, and creation of content is one of those, and AI is playing a much bigger role in that.

Microsoft’s obviously made massive investments. They’ve sunk a lot of their balance sheet into AI investments, and they are going to need those to pay off. So perhaps there are strategic business reasons why controlling people’s conduct on the desktop is important to them and that they’re able to kind of push their AI solutions to the forefront on those computers, even though users might not have otherwise chosen that. And then I think there might even be just simpler answers, is that there are executives at Microsoft that own, you know, own deliverable numbers on usage of Bing and usage of Edge. And those executives are going to do everything in their power to meet those numbers and exceed those numbers. And unless there is somebody telling them maybe that’s a bad idea or maybe that’s not worth it, they’re going to do it. And, you know, I think with the consent decree and the orders in the now distant rearview mirror for them, there probably aren’t as many people saying no in the company anymore.

[Bruce:] Yeah I mean 25 years – is there anybody left in the DNA of Microsoft who remembers those times? I don’t know.

[Gene:] There’s a few, there certainly are a few. But it’s it’s pretty clear that they have they have decided to take you know to to give a little more leeway to their to their executives to go do what they think they want to do so

[Bruce:] They’re they’re letting the Mr Hyde aspect of their character leak out.

[Gene:] Nobody liked to see lawyers in meetings back in those days, I can tell you. But at some point it became necessary to avoid the compliance problems and the fines out of Europe, and that sort of thing. But it wasn’t because anybody wanted us there to help them make decisions.

[Bruce:] I mean, I wonder because, yes, a lot of the focus has been on mobile over the last few years. And, you know, before I was with Vivaldi, I was waging a four-man battle against Apple and iOS. But I don’t think desktop ever went away. I think, as Mark Twain said, its demise was highly exaggerated. You know, maybe i’m a maybe it’s because i’m an old fella but yeah i’ll look at my phone to find out who an actor is when i’m watching the TV, or something like that but if I have to write something, I’ll go upstairs and use a keyboard just because of the form factor. I don’t think many mobiles at the moment have the power to run inverted commas AI to any meaningful degree and unlikely to from what we read about the power requirements. Talking of power, you said there’s nobody in Microsoft, or few people at the upper levels of Microsoft, telling executives to remember the Netscape case. Who is in a position to make Microsoft behave? Is it governments and regulators? Is it, are those the only people?

[Gene:] Probably so. I mean, there, there still are executives there that were there, then. I mean, Brad Smith is still there. He led the legal department through those compliance efforts. And so he understands it. The, but it’s going to, you know, I am a big believer in incentives and that people and companies act, in the aggregate, consistent with the incentives that you put in front of them. And if there is no disincentive, then companies will take every inch that they’re able to take, until the incentives compel them to do otherwise. And so I think that’s what we’re seeing, that there is no particular deterrent, given the lack of focus on Microsoft for quite a while, and that that deterrent will have to become real to them, in order to really change their behavior.

Now, given their experience, they may understand the deterrence a little earlier, perhaps, than some other companies we’re seeing in the news these days have done. But so they may snap to quite quickly if they’re faced with a little bit of scrutiny from regulators. But because… it didn’t happen overnight at Microsoft either that they became kind of cooperative with government officials on how to resolve matters rather than confrontational. I would say when I hired in there, my job was to be confrontational with with government lawyers. And my job eventually morphed into figuring out ways to work with government lawyers to get to an answer that everyone was satisfied with. But like I said, Microsoft probably got a little more experience there, so it might be a little quicker to comply. But there’s going to need to be some credible threat of action by government officials to actually change their behavior, I think.

[Bruce:] So you believe there might still be enough residual muscle memory inside Microsoft, that if there were a judgment or a requirement from somebody with a big enough stick that, they could?

[Gene:] Maybe even just a formal investigation might be enough to move them. If it moved along, the threat of even a formal complaint would probably get some people’s attention there and may or may not, might or might not, cause them to change anything. But there’s definitely still some muscle memory within the company, for sure.

[Bruce:] Is there the political will in the States and the EU, I think? Today is April 23rd, and the first fines under the DMA were announced against Apple and Meta: 500 million euros and 300 million euros respectively. Somebody calculated that Apple’s 500 million was nine hours worth of profit or something. So not a big deterrent. And given that the administration over on your side of the pond seems to not be particularly, doesn’t particularly like the EU as an idea, let alone the EU regulating US tech firms, is there appetite for regulating the behemoths, do you think?

[Gene:] You know, I think that there is. If you, you know, they may have their issues with particular actions by the European Commission. But on the whole, there is active litigation by the United States government against Google. Obviously, they’re in the midst of a great deal of courtroom drama. DOJ filed a case against Apple, which the current administration shows no signs of backing down from. And similar, you know, there have been cases brought. I mean, many of these cases, the Google cases, were brought by the first Trump administration, in fact, and continued under Biden and now presumably continued again under the second Trump administration. So there definitely is an appetite to rein in the power of these dominant digital platforms.

There’s rumors even that Microsoft is being investigated by the FTC right now. I’m not sure what the contours of that investigation are, but there are there’s every indication that they they don’t intend to back away from taking steps to rein in their power. I think they there may be some political back and forth over who ought to be the one doing it or taking the lead on that. But actually, I think there’s a lot of consensus around the world on the need to rein in the power, and maybe not always on the exact means of doing so, but it doesn’t seem like there is a substantive dispute.

I mean, take the Apple fine today, for example. They are being fined for disobeying the DMA’s requirements around the anti-steering provisions in their developer agreements. That’s conduct that has already been found to be illegal in the United States, too, and for which Apple may be on the verge of getting hit with a significant contempt of court order for defying the district court in the United States the same way they are defying the European Commission in Europe. So the fines are small initially, but I think if they don’t change their conduct going forward, now that they have been officially informed that they’re breaking the law in Europe, then I think we can expect probably those fines to escalate, the same way that, if they continue to defy the U.S. — a U.S. District Court judge in the United States, they will be hit with increasing penalties, too, to the point where I would be a little nervous if I was an Apple lawyer going to court to argue again, that you might have to bring your toothbrush in case the judge decided to send you to jail for a few nights.

[Bruce:] Don’t they provide toothbrushes?

[Gene:] I think it’s like the ones they give you on the airplane. It’s not one you necessarily want to use. Yeah. I believe that.

[Bruce:] I believe they have them in UK prisons, but, you know, I only believe this. I have no experience thereof. So what next for the Browser Choice Alliance? I mean, you’re an advisor to the Secretariat. You’re not one of the browsers that are going forward. But we’ve spoken to the CMA, that’s the Competition and Markets Authority, here in the UK, towards the – was it last year or this year? I can’t remember now.

[Gene:] I think it was December. Yeah.

[Bruce:] Yeah, the weather was foul, but then it’s United Kingdom. So, you know, that’s any month apart from June. And we’ve spoken to the EU. The wheels grind slowly. The CMA has investigated Google and Apple. So presumably Microsoft should be on its list, we would hope. It’s big. It’s misbehaving. What would you expect? What would you hope to see next, Gene?

[Gene:] I think the hope is, and, you know, reminding all of these authorities, UK, EU, US, and other places in the world, that Windows and Microsoft never went away. That this was a problem to some degree that was solved in the early 2000s. Now, people will disagree as to whether it was truly solved or not, but it was solved enough that Google Chrome became the largest browser in the world on PCs instead of Internet Explorer and then later Edge. So it was solved to some degree at least. And that if they take their eye off the ball, they will have to they will have to re-solve that problem. So I think it’s putting this back on the radar of enforcers, getting them to pay real attention, getting them to inform Microsoft that they’re taking it seriously. And at that point, we will see whether Microsoft wants to fight, or come to the table and implement a lot of procedures and technology that were present in the early 2000s that could be, again, quite easily, but that will enable user choices to be respected, and enable third-party browsers to compete on its level of playing field as a regulatoe can create for them.

[Bruce:] And there’s something happening in Australia, isn’t there? We’ve written to the Australians.

[Gene:] There’s action in, I would say, there’s interest in Brazil, Australia, Japan, around the world in many jurisdictions. And perhaps none of those by themselves are enough, but all of them have at least a significant enough market for Microsoft that they’ve got to pay attention. And like many of these things, once one jurisdiction starts something, others tend to follow along or to say me too. I mean, we’re seeing that to some degree with Apple’s situation now where I think every jurisdiction around the world has kind of reached a consensus about Apple’s App Store conduct. And now it’s a matter of how do we resolve that around the world, instead of piecemeal actions. And like I said, that’s the difference I see, I potentially see between the way Microsoft might respond to some formal investigations by trying to resolve them before the fight is fully engaged, whereas Apple seems quite content with engaging the fight all the way to perhaps the bitter end, we will see.

[Bruce:] Well, they’ve always been like that, haven’t they? There was a really good interview that I’ll put in the show notes with a guy who used to be Apple’s chief counsel, saying, Steve Jobs and Tim Cook would say, fight right up to the end. They have a billion or something. The guy’s name is Bruce, which upsets me, you know, being a good Bruce. So all of this, hopefully then we’ll see Microsoft open its closet and find its long-lost halo, and turn out good. Will the next time I see Gene Burrus, you’ll be head of implementing all the stuff at Microsoft again?

[Gene:] I don’t think it’s in the cards that I’m going back to one of those big companies. I kind of enjoy bringing the fight to them, actually. And so I don’t foresee that big tech platforms will leave me without any issues to go after for the next decade, at least, I would say. If I want to work that long. And since I did work during the Cold War, I’m kind of hoping retirement might come before the next decade is up, but we’ll see.

[Bruce:] Yes. Well, yeah. Every time I get close to retirement age, they raise the retirement age. Why do you like bringing the fight to big tech, Gene?

[Gene:] You know, it’s something I’ve developed a bit of a passion about. So like I said, when I was at Microsoft, you know, I hired on there to be first the guy that wrote nasty letters back to the DOJ telling them why they were wrong and couldn’t force us to do what they wanted us to do, and then dealt with the compliance angle. But I really, really found my stride a little bit when I figured out that the worst possible outcome for Microsoft, who I was working for at the time, the worst possible outcome of those antitrust decisions that they lost were that they only ever applied to Microsoft, and not any of its competitors because they would be constantly you know, battling with one hand tied behind their back, if that was the case. So it’s almost like equal protection under the law applies to corporations too. And that if, that if those were the rules, that’s fine, but then everybody ought to apply, ought to, ought to play by those rules. And so got to go, you know, got to go engage with a lot of the regulators who I had been arch enemies with for years and got to go in and talk to them and have I got a case for you? You know, because it was as Microsoft’s competitors started to gain their own degree of power in the relevant in their markets where they were operating and where Microsoft was kind of the upstart or the struggling entrant, search being a good example of that, to go make sure that as much as possible, that those laws were applied equally, and that people could compete on these platforms on as level of playing field as you could try to make them.

I also have come to the conclusion over the years that these platforms are a little different than the old monopolies under antitrust law where companies with monopolies, you know, whether it’s U.S. Steel or whatever those companies were, They had monopoly power. They had the power to raise prices and limit output in particular markets, which is bad for consumers. Yes, they have to pay more, but that’s kind of the limit of their power back then, right?

Today, these companies, especially in the digital space, have a lot more than just power over output in prices in a particular market. They have the power to control access to information, and the power to control the outcome of elections and other things like that, which is so far beyond, you know, the economic market power that antitrust lawyers used to worry about that it’s, you know, I think it’s vitally important that the power of these digital platforms be appropriately limited so tha consumers and businesses can do business on them. but that we don’t end up being governed by a few executives in Silicon Valley. And so I’ve kind of gotten a passion around that, and I would like to continue making sure that as best we can, we can control that corporate power.

[Bruce:] I completely agree. So here we have a middle-aged ex-punk rocker from the UK, and a besuited, not now, but erstwhile-besuited Microsoft lawyer agreeing with each other about fighting the power to protect consumers and protect digital rights, really. Access to information is paramount.

[Gene:] Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I think that’s what I say. I think I think it’s it’s a very important issue. It’s one that I feel good about getting up and working on every day. And, you know, that hasn’t always been the case throughout my life. I mean, my first job, literally, that I walked through the door at General Dynamics back in 1986, was to design the mounting bracket for a nuclear warhead on a Tomahawk cruise missile that was going to be driving around the roads of Europe on the back of a tractor trailer.

[Bruce:] I left my first corporate job because we got taken over by a company that made guidance systems for missiles. And yeah, since then I found the web, and been fighting the man ever since. But yeah, I mean, it’s not just fighting the man and protecting people. It’s about, I think, it’s about protecting tech. I was very struck when I was reading the case against Apple that’s, I suppose, been bought by the DOJ. (It’s unclear to me who brings these cases.) But there’s a sentence that really resonated with me. It said, you know, Apple’s behavior now would restrict the ability of another Apple ever to rise again in the market. Who knows how many really great companies have been drowned in a bucket by the big guys.

[Gene:] Well, that’s exactly right. I mean, if you think back, there are varying views on the success or failure of the case against Microsoft in the early 2000s. And it obviously, you know, the ultimate outcome of those cases came too late for the names like the names that brought the cases, like Netscape, Real Networks, Sun Microsystems. All were of limited relevance by the time the cases were resolved. However, you could say they failed because those companies were dead and gone before they were resolved. But what it did do is create an environment where companies like Google and Apple could build the biggest businesses in the world on serving customers almost entirely on PCs in the early 2000s. So, you know, 90, 95 percent of Google’s revenue probably flowed through a Windows PC. And Microsoft was not in a position to either tax that revenue or otherwise kind of thwart Google’s business or their ability to interact with customers on a PC. Similarly, Apple was kind of a dying company in the early 2000s, on the verge of bankruptcy. And it was literally, it was the fact that they developed the iPod, which was a cool new device that everyone wanted. But at first, they could only sell those to customers that owned the Mac. That’s a pretty small addressable market for them. Then, but they were able, in large part because of the antitrust cases, they could put iTunes on Windows, sell iPods to every PC user in the world, and kind of the rest is history, right? That was a wildly successful business that funded development of the iPhone, but led to the iPhone, which if you recall back in those days too, the iPhone required iTunes in order to sync on your computer when, you know, the first few versions. Would that have been possible if Microsoft could have interfered with Apple’s business on PCs? You know, I think we might be using Microsoft phones instead.

[Bruce:] That’s right. We’d be listening to our Zunes.

[Gene:] Yeah, exactly. Now, I happen to like the Microsoft phone and I like the Zune, but obviously the market chose otherwise. But it’s definitely the case that a similar situation can emerge today that if these companies aren’t constrained, who knows who the next Apple and Google are, but we’re not going to find out if those companies are able to basically either kick those companies off of mobile devices, or are able to tax them to death, or take the lion’s share of their revenue just because they own that gateway. The same way Microsoft could have in the early 2000s intervention and quite frankly the same way Microsoft could again on PCs if they’re not constrained.

[Bruce:] Yeah. Gene, I have one more question to ask you, and it’s nothing to do with tech. But I’m a great fan of courtroom dramas, and I asked some lawyers from the Department of Justice for this favor and they look pretty bewildered and hung up pretty quickly but would you mind yelling “objection your honor!” for me?

[Gene:] I can do that, I’ve done that in real life a few times, so yes: objection your honor!

[Bruce:] Sustained! [accidentally hits microphone]

Thank you Gene Burrus of Burrus Competition Strategies, thank you so much for spending time talking to us, and thank you for fighting for a better web

[Gene:] Thank you it’s great to be on, and a great conversation thanks.

[Bruce:] Brilliant, thank you Gene. All right, speak to you next time listeners. Thank you for listening.

Show notes

- Burrus Competition Strategies

- Gene on LinkTin

- Browser Choice Alliance

- United States v. Microsoft Corp (“Netscape case”)

- Vivaldi’s Open Letter — Microsoft DMA Compliance

- Microsoft Edge pseudo-protocol

- Commission finds Apple and Meta in breach of the Digital Markets Act

- Vivaldi’s statement on Apple and Meta DMA anti-trust fines

- Bruce Sewell, Former General Counsel of Apple Interviewed

- “Competition is what will ensure that Apple’s conduct and business decisions do not thwart the next Apple” from DOJ and States v Apple

- “Objection, your honor!”