In this podcast series, Bruce interviews people from across different communities and industries who, in their own way, are fighting for a better web.

Bruce chats with Andy Yen, founder & CEO of Proton, about what it’s like for a European company to take on Big Tech. Andy tells his story from leaving CERN as an ex-particle physicist, to building one of the world’s most trusted privacy companies in the world.

The former physicist breaks down the VPN industry lies, why most companies can’t be trusted, and how Apple and Google’s 30% tax inflates your bills. He also explains Europe’s trillion-dollar tech mistake.

From VPN marketing lies to Swiss privacy laws, European tech independence, antitrust politics, trillion-dollar tech mistakes, and Proton’s plan to tackle tariffs and big tech “taxes”. This episode is an umbrella-drink filled to the brim with hot topics, you want to sip all summer long.

Transcript

[Bruce:] Hello, everybody, and welcome to another episode of the For a Better Web podcast, in which I, Bruce Lawson, Technical Communications Officer at the Vivaldi Browser, talk to somebody who, in their own way, in their own industry, is working to make the web a better place. And this time, it’s my great pleasure to be talking to Andy Yen, the CEO of Proton. Hello, Andy.

[Andy:] Hi, Bruce. Thanks for having me. It’s good to be on the show.

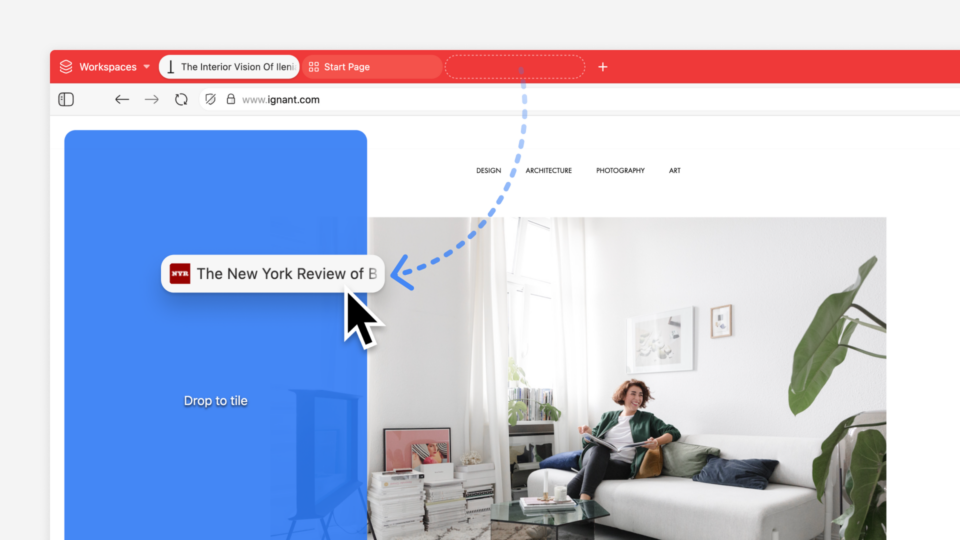

[Bruce:] It’s great for you to be here, too. I should say to our listeners, full disclosure, Proton and Vivaldi have a relationship because if you’re a Vivaldi user, you’ll know that we recently integrated Proton’s free VPN into Vivaldi desktop. But I’ve wanted to speak to Andy for a long time. I’ve been a Proton user for quite a long time now on the recommendation of my cousin, who’s a VPN researcher. So just putting that out there so you know the relationship between us folks.

So, Andy, you are a physicist, I believe. You were working at CERN. So how are you running a VPN?

[Andy:] Well, I think Proton is much more than a VPN. It didn’t start with a VPN actually. I think the connection between CERN and the web actually goes quite far back. If you back in 1991, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, when he invented the web, was actually working at CERN. So there’s always been an intercession between science and technology, and CERN in particular, because of the massive amounts of data that we deal with, and the infrastructure that is built to support that, actually has a very good connection.

So I would say that working in science, the topics around privacy, security, these are things that come about because as a scientist, well, you don’t go into science to make money, right? I can tell you there’s not a lot of money in science.

You do it because you wanna work on some of the world’s most interesting problems or the world’s most difficult problems that you think actually benefit society. And if I look at society today, especially back in 2014, when we started the company, One of the big things was, well, you know, the web as we know it is sort of going in the wrong direction. It’s something that is increasingly monopolized by a few big tech companies that really don’t have the best interest of society and users at heart.

So our challenge, our motivation was to figure out how can we build a different model of operating online, which goes against that and actually brings privacy, freedom and choice back to Internet users.

[Bruce:] That’s cool. Were you a physicist at CERN? Were you working on small particles?

[Andy:] Yeah, actually, I was a particle physicist, and I was working on a part of particle physics called supersymmetry. And so actually, my PhD is in physics, indeed. And I guess I’m one of the many physicists that ended up in tech. It’s quite interesting because had we found supersymmetry and had we found new physics of the Large-Hersion Collider at CERN back in those days, probably Proton wouldn’t exist. Probably we would all be professors somewhere doing research into new physics.

But it turns out that the nature of the universe was that the LHC, the machine we’re working on, was not big enough to discover new physics. So in some ways, the nature of the universe caused Proton, the company, to be created because all these great scientists suddenly had a lot of free time. The field was less exciting after we did make the discoveries that we were hoping to make.

[Bruce:] Gotcha. And is that why Proton is called “Proton”, as a nod to the Large Hadron Collider?

[Andy:] Yeah, it’s correct because it’s the LHC, the Large Hadron Collider, it’s actually a proton-proton collider. So we were smashing protons and we thought, OK, well, that’s a good name. Let’s use that.

[Bruce:] Great. Thank you. I love theoretical physics, even though my degree is drama and English literature. So I have no mathematic ability, but I’m fascinated by it. In fact, D.H. Lawrence wrote a poem about relativity in the late 20s, interestingly. Anyway, I know nothing at all about the tech behind VPNs. And I know Proton isn’t only a VPN, it’s how I first encountered you.

So I asked an expert, my cousin, Simon Migliano, from Top 10 VPN, for a tech question. And he said, Ask Andy this. The VPN space is full of marketing claims that don’t hold up under scrutiny. What should users demand as proof of trustworthiness in a VPN? And how does ProtonVPN meet that bar?

[Andy:] Yeah, I think that’s a very interesting question. It’s fascinating because if you look at the VPN industry today, I would say most of those businesses are not tech businesses, right? They’re probably marketing businesses and in many cases, exceptionally good ones at that. And I think in some ways that’s always been what has made Proton different.

[Andy:] Fundamentally, when it comes to a VPN, what you’re doing is you’re saying, I don’t trust my internet service provider. And I’m going to trust some other guys. And the other guys is the VPN company. And it’s interesting because a lot of these VPN companies out there, you don’t even really know who runs it. And then when you do discover who runs it, you probably think to yourself, well, these guys probably shouldn’t be running a VPN because I can’t trust them at all.

And it’s interesting, if you dig in a lot of VPN companies, there’s a lot of stories of, you know, well, people that were from the ad tech or malware space that decided to go into VPNs, right? Which, you know, doesn’t make any sense.

So, you know, software at the end of the day, we think about it as code, but actually you’re trusting, you know, who writes the software. So I think one of the key things that’s very important is you need to look at who is building the software that you’re running, what is your motivation, what is your credentials, and why they’re actually credible in doing what they’re doing. So I would say in the VPN space, look at who’s behind a VPN company. This is the key thing, right? In a lot of cases, you can’t even find it, which is the first problem.

But beyond that, I think it’s also important to use VPNs that are open source. So you can actually validate that it’s actually working as advertised and that, you know, and there’s a level of transparency that comes from having clear ownership, clear disclosure of who’s behind it, and clear ability to inspect the code that I think are very, that is very essential. Because VPN at the end of the day, it’s a trust business. And, you know, trust comes from transparency.

[Bruce:] Yeah, yeah. And same with browsers, same with almost anything that sits between you and the wider web out there. So if it’s to do with researching credentials, you’ve got to be pretty savvy to know how to do that. And VPNs are becoming more and more mainstream. It used to be computer geeks only, but now more and more people, normal users, regular users using VPNs. Is there any sort of magic thing they can do to find out the credentials, or is it just Googling, Binging, Yahooing?

[Andy:] Yeah, it’s actually a very interesting space as well in this regard because a lot of the – well, it’s just publicly out there now, right? You know, a lot of the, let’s say, most well-known sites that review VPNs are actually themselves owned by the VPN companies, right? And there’s a few prominent examples of this out there in the industry. Then you might say, oh, maybe I’ll go to, you know, my YouTube influencers. But, you know, half of them are paid off by VPN companies as well, right? You’ve been on YouTube, you’ve seen all the ads.

So I do think there’s a big credibility gap, right, about who you can believe. Because in fact, advertising is so subtle these days that you’re not sure if they’re saying it because it’s true or they’re saying it because they’ve been paid to say it. And yeah, so this is why I think it’s important for users to be savvy, right? You’ve got to do a bit of digging, try to understand a bit of the space. And I think also do your best to research who’s behind these companies, right? And don’t just click on the first thing that you find online because odds are that it’s not an impartial review, right?

And yeah, so I think it’s a bit too bad that this is the nature of internet today. It’s not just VPNs, actually, but, you know, whether antivirus or any other business out there, it’s kind of the same, right? You know, we’ve sort of lost the really, truly impartial reviews. And so I think it’s, this is why, you know, word of mouth, talking to experts that knew, you know, I think everybody always has that one friend they know who is, you know, the person that knows all the tech things, right? You know, ask that person, right? Because he probably has done more research.

But yeah, I do think consumers say you have to be careful about who they pick, whether it’s your browser, whether it’s your VPN, whether it’s email service. There’s usually more than meets the eye.

[Bruce:] And in answer, I guess the second part of that question, how does Proton meet the bar? I suppose you kind of answered it in the sense that you’ve said the source code is open source.And whereas not everybody is adept at reading C++ or something. The fact that you put the source code out there indicates, you know, that a wish for transparency. And also you are a not-for-profit, I believe. Is that correct?

[Andy:] Yes, that’s correct. And actually open source, the benefit of open source is not that you personally can go and inspect the code and understand it because odds are that, you know, you can’t, right? The benefit of open source is that anybody that wants to can go and inspect the code and look at it themselves.

[Andy:] And even if you yourself cannot read the code, it’s very likely that among the 8 billion inhabitants of Earth, there is someone out there who can read it and has done it. And if you’re a big enough VPN player and there’s something hiding your code that is, let’s say, not kosher, it’s going to get found if it’s open source code. So I think, you know, open source, even if you personally cannot read the code, is still actually valuable, you know, for that reason.

[Andy:] And I think also, you know, Proton’s structure is also something that’s quite unique in this space. Today, the main shareholder of Proton, actually the controlling shareholder, is the Proton Foundation. That’s a nonprofit that’s based here in Geneva, Switzerland, whose mission is actually to further online freedom, privacy, and democracy.

[Andy:] And this, I think, is something quite important because today your data online, actually, it’s being sold to the highest bidder. Even a company that is a privacy company could get sold to a bigger company that doesn’t care about your privacy anymore. And I think an example of this is recently 23andMe went bankrupt in the US. That’s a DNA testing company. Well, guess what? In a bankruptcy, the highest bidder bought your DNA data.

So I think the fact that we’re a foundation means that it has a long-term guarantee that actually Proton cannot be sold because the foundation’s mission does not allow it to sell it to the highest bidder. And this is sort of the strongest reassurance that you can possibly have, right? Anybody else out there that’s in the VPN space or in the privacy space, actually, they’re going to be for sale eventually.

And I think we did that structure because it’s the only way to ensure in the long run, doesn’t matter what happens to me or the other people in the company, the foundation will always be here, always ready to defend the mission and defend user data in the long run.

[Bruce:] You sound very passionate about this, Andy. What drives your passion for transparency? And you mentioned democracy two or three times. What is it that drives you personally?

[Andy:] Yeah, well, I think, first of all, I’m a scientist originally. And I think no matter what you do in life, you always stay kind of a scientist. And if you know about science, the core essence of science is peer review, right? It is coming up with an idea, but then having other people validate it by publishing your work openly, so that the rest of the world can challenge, discuss, and validate the research that you have done.

And today, if you look at Proton’s office here in Geneva, for example, probably a third of the engineers here came from CERN. They’re scientists as well. So I think that scientific ethos is very strongly in our culture. And this is why we’re transparent. This is why we’re open. This is why we publish what we have done. This is why we publish our code. Because that is simply the way that we’ve always lived our lives.

[Andy:] If I zoom out a little bit more, I think there’s maybe two other things that motivate me. One, I’m originally from Taiwan. And that is quite close to a neighboring country called China.

[Bruce:] I’ve heard of it. I’ve heard of it.

[Andy:] Yeah. And if you’re neighbors to China, and technically still at war, in fact, right, because the war was never settled, you understand very quickly how freedom can disappear if there’s no privacy, and how democracy is not something that you take for granted. So I think that background also makes me maybe a bit more sensitive to these issues. And this is why I believe strongly in privacy, freedom, and democracy, because I think actually the three things are entirely linked. So I think that’s definitely one factor.

The other factor that really motivates me is if I were to go out today and talk to the average online internet user, which is basically everybody today, right? and I were to give them Google’s vision of the web and also share with them Proton’s vision of the web, I would wager that probably 9 out of 10, or maybe even 99 out of 100, would say that they’re more strongly aligned with Proton’s vision of what the web and what the internet can and should be.

And that is, for me, extremely motivating because from that alone, I think in the long run, we’re going to win. And, you know, it’s a lot more, let’s say, easy to get motivated for a fight if you believe that you can win it. And I do think that we can win it in the long run because the vision that we have of how the web should be, this is what consumers actually want. And so, you know, now we have to work hard to make it possible, right?

[Bruce:] Music to my ears. So one of the reasons that you’re so strongly into transparency and openness is because of the scientific method, because it depends upon attempts to falsify hypotheses. And if you can’t access the methods and the results and the experimentation documentation, you can’t do science, I guess.

[Andy:] Yes.

[Bruce:] Is that why Proton is headquartered in Switzerland now? Because that’s where CERN is and it was easy to get people. Or is there something specific about Swiss historic neutrality, Swiss civic society that made you want to be there?

[Andy:] Yeah. Well, it was almost kind of a historical accident in a sense because Proton was, in fact, built… the first version of ProtonMail was coded up in the CERN cafeteria, right? So we were already here and when we needed to decide where should we place the company in order to give the best protection for users. And you look at all the legislation that exists in the world, actually Switzerland was one of the best locations.

Now you can probably find one or two, you know, random countries somewhere where there’s a total lack of regulation where anything goes that, you know, maybe even more private on paper, but they’re not places that you can incredibly run a business. And of course, there’s also some folks that say, oh, maybe you should put your business offshore somewhere on a Caribbean island or 15 miles from the nearest landmass. But that’s not practical either.

So in terms of, let’s say, well-developed countries that have the scale, but also the legislative framework that allows privacy services like Proton, which are based on trust, to really, let’s say, service users globally in a very good way. Switzerland is one of maybe a handful of countries that I think meets the criteria. So that was why at that point we decided it makes sense to be here.

But what I want to stress is I don’t think you can build your company fundamentally around the laws. Because laws can change and governments can change. It takes just an election, as we’ve discovered in many countries around the world. Right. So I would say that, you know, the protection that you get from Proton is less about the laws of Switzerland and more about the laws of mathematics, the laws of encryption, because I don’t care who wins the election. The laws of math are not going to change. And that’s a guarantee that we want to give to our users.

[Bruce:] So protected by the laws of maths. Although talking of legislation or at least ordinances and application of rules, I read recently that Switzerland looks like it’s on the cusp of potentially a change in the regime of privacy and transparency. What can you tell us about that? Is it going to happen? Are you involved with that?

[Andy:] Yeah, it’s an issue that we’re watching very closely. What is going on is there is a proposal to revise the ordinance around surveillance. And what this revision would do is it would give the government’s, of course, ability to request more data from companies like Proton. But it would also require us to retain metadata. So it would bring mandatory metadata retention into Switzerland. And for me, this is very troubling because actually today, mandatory mandatory retention, this has been ruled illegal in Europe. It’s not even done in the US, right?

So Switzerland will be introducing something that on this continent, the only country that does it actually is Russia. And I think it’s the wrong direction for the country, right? So obviously, you know, at Proton, together with allies, we are fighting this. And we’re fighting it now through the, let’s say, through the public consultation that is being done, and we’ll also find it in the courts as well, right?

Do I think this thing will, you know, make it all the way through, you know, passing the consultation and also passing the court challenge that we would mount? I would probably say if I had a bet, no, right? But you’re never sure. So you have to fight it anyways.

And I do think it’s important to fight measures like this because you see more and more in different countries around the world, you know, attempts to weaken encryption, attempts to put more surveillance. And this is the slippery slope. This is quite dangerous, and it simply doesn’t end well.

And the way to look at this is, let’s say even if today you happen to trust your government, well, a couple of years from now, or a decade from now, maybe an election happens, and there’s a government that you don’t trust. Well, at that point, what are you going to do? Are you going to say, oh, I don’t trust you anymore. I’d like to take back this power that I gave you 10 years ago.

That’s never going to happen, right? So the only guarantee that us as citizens have that our data will stay safe is if we have a legal framework that protects us irrespective of who is in power. And this is why I think legislation, our changes in legislation and ordinances, which weaken encryption, it’s something that it doesn’t matter which political side you’re on. It doesn’t matter if your guy is in power today or not. We should all be incentivized to fight that.

[Bruce:] Maybe this is asking you to speculate, but i imagine that the the government has explained why it wants to change these ordinances what is the impetus for this potential change?

[Andy:] well actually, the way Switzerland works is these ordinances can come from an administrative unit and someone simply makes a proposal to change it and then it can kind of go under the radar and actually slip through all the way. So this is maybe, in my opinion, a failure of the Swiss way of doing ordinances because you could really have just one insane person sitting in Bern come up with an extreme proposal and that proposal could, if no one pays attention, go through and become adopted.

And I think the way that I would look at this is if you were to ask the policeman to write the rules, it shouldn’t surprise you that you end up living in a police state. Right. So what I think happened here was people, in fact, I know exactly who, was asked to update the rules. And this is someone with a very extreme view of surveillance. This is someone that would probably be a natural to work in Russia, for example. And he simply imprinted his extreme view onto the ordinance without any consideration at all to the economic, social, and political effects. And luckily, we were able to catch this, raise the alarm, make a lot of noise. And what is amazing is almost all the major political parties in Switzerland have now come out against this revision. And so hopefully we stop this thing.

But I think this is why, you know, in this space, in as citizens, we need to be constantly vigilant, right? Because instantly we look away, something like this can slip through. And we got to pay attention. But yeah, if you let a policeman write the rules, don’t be surprised to wake up in a police state. This is, I think, the simplest explanation of it.

[Bruce:] Yeah, I hear you, and good luck with the fight. Here in the UK, our government is attempting to weaken encryption because, you know, child abusers sometimes send images through WhatsApp. Therefore, the government should be able to snoop on everybody’s private messages. And, you know, if you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear.

[Andy:] Yeah, and look, at Proton, actually, we take a very strict rule on this, right? Like, you know, let’s say we’re not successful in fighting this and this goes through. I’ve already stated publicly and I’m happy to say it again. You know, we will leave Switzerland if this passes. Right. And I think actually it was important to say that because that was what made what was, you know, could have been a technical issue that was ignored into a political issue. And, you know, I’ve been very, let’s say, positively encouraged in the last few weeks and months to see sort of all the political and economic actors in Switzerland aligning around our positioning and fighting this.

[Andy:] So, you know, I think we’ll see in the next 6, 12 months what happens. But if I had to bet, I would say that probably we’ll succeed in blocking this.

[Bruce:] It’s nice to see that Proton is fighting for what it believes, because a lot of tech companies fight for what they believe, but what they believe is basically the right to profit off other people’s data. Vivaldi doesn’t and Proton doesn’t. It would be wrong to characterize you personally as anti-regulation, though, wouldn’t it? I believe you quite vehemently support regulation of tech.

In fact, some people were surprised recently that you supported somebody called Gail Slater, who was a Republican nominee to lead antitrust in the US. Antitrust, of course, is a political hot topic globally. How does Proton and how do you, Andy, navigate your way through the political turmoil that’s going on at the moment? And what’s your position on regulation and Ms. Slater?

[Andy:] Yeah, I think it’s very tempting to say, oh, you know, politics is a mess. Let’s stay away and don’t get involved at all. But I do think companies like Proton have to stay engaged. And we cannot just bear our heads on the ground and say it doesn’t matter. If we don’t care, it’s whatever. So I would say it’s absolutely essential that we politically engage because that is the way in which policies are changed.

Now, U.S. politics is kind of interesting because it keeps flipping back and forth. Democrats, Republicans, right? And yeah, some people were surprised that I was supportive of a Republican nominee. But actually, in fairness, four years ago, I also supported the Democrat nominee, right? So had I not supported Gail Slater as nominee, maybe I would have been biased. But you know, I didn’t support her, actually, because I wanted to be neutral, right? And to also back both sides. Now, I supported her because I actually think she’s a good nominee. And if you look at the confirmation votes, she had, I think, 78 votes in the US Senate, which is ridiculous because nobody gets 78 votes in the US Senate. It’s completely divided. And what we saw was actually a lot of the Democrats who are most strongly in support of regulating big tech companies antitrust, like Elizabeth Warren, the senator she also voted to support Gail Slater. So it’s not just my opinion, actually, it’s opinion of quite a few Democrats and Republicans that she’s a good nominee.

What I find interesting is that we used to think anti-trust was a partisan issue. But actually, I think antitrust is a bit like privacy now. It’s really something that people on both sides of the political spectrum should be able to support, because big tech companies being too big and dominating society and politics, this is not good for the world. I don’t think it matters whether you’re a Republican or Democrat, you should be willing to stand against that. And so, you know, from that perspective, I think when you have people in government, irrespective of their, party affiliation, that seem to be committed to doing the right thing and want to push through changes.

And if you look at what’s going on in the US today, they are still litigating and taking, you know, legal action against big tech companies, right? Sure, now it’s under the Trump administration that’s doing that. But I think we should support that effort, because that effort is extremely important in creating, let’s say, a better internet economy for everybody. And, you know, I think there’s some subject to developments at a US recently. And I think the US, we have to pay attention to, we cannot ignore and disengage, because at the end of the day, these are American companies.

And I’ll give you kind of an example, right? Apple and Google do this crazy thing where they’re trying to take 30% fees of revenue from every payment that you collect on mobile, right? And, of course, can you imagine an industry where you’re trying to compete and you have to pay your base on 30% of your revenue? It’s impossible, right? And the European Union has been fighting this for probably five or six years now.

They even passed a new legislation just to enforce this, right, called the Digital Markets Act. And even with the new legislation and all the things they’re doing here on this side, they still have not succeeded. What actually changed for the first time, you know, was a court order in the U.S. against Apple. And that caused Apple to roll back its policies around 30% fees in the US, right? So I think this is evidence that actually a lot of these things, because these American companies, have to start from the US. So if you believe in making a change here, it’s not possible to disengage from the US. You’ve got to fight the fight there, because that is where you will, realistically speaking, have the biggest impact.

[Bruce:] Personally, I completely agree. I’ve been fighting Apple and Microsoft now for four years. I engaged in a short-lived, interesting lockdown project to engage with the regulators. And that’s been four years. But it seems ironic to me personally that we regard Europe as sort of the place where things are regulated to death. and we regard The States and particularly, you know, Mr. Trump and the Republicans, the place where it’s they hate regulation and everything’s going to be a free for all. But the most important acts have come from that Republican, or at least, under the Trump administration. He started the DOJ versus Google case in Trump 1. I wish we were seeing similar stuff in the EU personally.

[Andy:] Yeah, well, I think the EU is trying its best, but they don’t quite have the tools to do it. And, you know, these companies are American companies, right? So they can very easily or more easily, let’s say, give the finger to EU regulators. But they cannot defy American court orders that easily. And this is what we saw in the Apple case.

[Andy:] I think it’s an interesting point you bring up because indeed, you know, the antitrust cases that you mentioned were started by the first Trump administration, but they were also continued by the Biden administration. And now the second Trump administration is still pursuing them. And this is why I think, you know, we need to not make antitrust a political issue. It’s like privacy. There should be a bipartisan consensus, regardless of your political leanings, that says this is something that we should pursue because it’s good for society. And, you know, it’s very hard in today’s polarized world to find common ground. But I think that is one issue where it is possible to find common ground.

[Bruce:] I agree. Personally, I think, and again, you know, I’m speaking as Bruce rather than Vivaldi here. Personally, I think if you cannot support somebody because of the color of their political rosette, even if they’re doing something good, that isn’t neutrality. That’s utter partisanship in and of itself. I’ll support somebody who wants to do the right thing regardless of what their political affiliation is personally but yeah

[Andy:] Yeah and i think that’s the objective way to you know look at it. But of course, the politics can also be very emotional and it’s hard to see reason sometimes right but but but indeed i think you know as players who are in it for the long ru,n we have to stay very rational and we have to figure wins when we can get them right it doesn’t matter, you know, kind of which party they’re with. And I would say if you look at just going back to kind of Gail Slater, right, that was probably one of the best possible picks that we could have gotten out of the possible roster of Republican antitrust candidates, right? So I think, you know, I’ll take the wins when I get them, because there aren’t that many wins, to be honest.

[Bruce:] There are not that many wins, but hopefully there’ll be more. Apple likes to say with the 30% app store tax, Apple likes to say, well, it doesn’t hurt consumers because developers pay. Now, you’re a developer. What’s Proton going to do now that you don’t have to pay 30% tax to Apple?

[Andy:] Well, you know, that’s a bit like Trump saying tariffs don’t hurt consumers because it’s the companies that pay, right? There’s no difference between Apple’s 30% tax and a tariff. If you’re charging companies 30% more to sell stuff, there is no question that’s going to get passed on to consumers. The idea that companies can just absorb 30% hit on their margins and just walk away, it’s as absurd as saying automakers are going to absorb 30% tariffs and not pass them on.

So for sure, the Apple tax is paid by consumers, by American citizens. And this is why even if you’re an Apple fan, you should be against the Apple tax, to be honest, right? Because it’s going to reduce your prices. What we’re going to do in the US is on some of our services, like our VPN service, for example, we’re actually going to drop prices 30% and we’re going to pass on those savings to the consumers.

[Andy:] It’s the right thing to do. And I think it’s important to highlight just how abusive the Apple tariff is, and how much it is increasing the cost, right? I was telling some people in the US, like we talk about like inflation being a problem in the US, right? This is actually, it’s a problem in Europe as well. Well, if you want to cut inflation, getting rid of the Apple tariff, that’s a good way to start because everybody buys services online now, right? Everybody buys things on mobile. And, you know, I think practically every American is paying this indirectly. You just don’t realize it.

[Bruce:] That’s, yeah. And it’s a great message to say, you know, look, we are passing on this discount or this reduction to our consumers because it was them who was paying it in the first place.

[Andy:] Yes, yes.

[Bruce:] Poor Apple.

[Andy:] I don’t know. I wouldn’t shed a tear for them. They have trillions in market cap, hundreds of billions in cash on their balance sheet. Honestly, they’ve been fleecing people for the last 20 years, right? So I think it’s time that they played fair, honestly.

[Bruce:] 100% agree with you. Why is it, Andy, do you think that the big tech behemoths are based in the US? Because occasionally people accuse me personally in my personal agitation and work of being anti-American. I’m not. I’m anti big tech, you know, crushing the neck of small tech. It’s a coincidence that that big tech is largely from the US. You know, ByteDance, of course, is not US. But is there a reason why we haven’t seen any, you know, comparably sized, comparably successful European tech companies?

[Andy:] Yeah, I think it’s an interesting point. And I can, you know, actually, I’ll tell you kind of a bit more of maybe the inside half of this. Fundamentally, it’s a first-mover advantage.

[Bruce:] Right.

[Andy:] Because the internet, if you will, was invented, let’s say, in the States. Not by Al Gore, as he claims, but it originated in the States.

[Bruce:] It was ARPANET, wasn’t it?

[Andy:] Yeah. And a lot of the infrastructure companies that powered the internet revolution, whether it’s chip makers or the other companies, they were originally from the States.And the reason they originally from the States was because back in those days, you know, the other major powers, you know, in the world was, well, Russia and China, which was under communism back in those days, not the most innovative economies in the world.

Right. So, I think it’s not it should not be surprising why big tech became big and came out of the US. What I think is the more relevant and interesting question is why is it that 30 years later, Europe doesn’t have a comparable tech champion, whereas China does? So what did China do right that Europe got so terribly wrong? And I think it really comes down to the European political mindset around investment, investment in the past 30 years.

So the way we should look at this is politicians in Europe had a choice in the late 90s, which is the exact same choice that their Chinese counterparts had in Beijing. Right. And that was “we’re behind on tech. We’re not the first mover. How do we catch up?” Well, the Chinese took the decision that “technology is a matter of sovereignty for us. It’s a matter of our future independence. And it’s a matter of our future economic growth. So no matter the cost, we must build that domestically”.

And what Europe did differently was they said, you know what, it’s going to be cheaper to buy American tech. So they traded a short-term cost savings for long-term strategic mistake that today is costing us in Europe way more money than we have saved by adopting American tech. So it’s really a difference in mindset that caused this catastrophe, right? Because actually, we were ahead of China, in fact. So how did China get ahead of us? It was simply a different policy at the government level.

[Andy:] And this is what I think needs to change in Europe in order to turn this around, right? Every single time a government agency, a school, a university in Europe is buying from Google or Microsoft, what they are doing is they are mortgaging the economic future of the next generation of Europeans for a short-term cost savings.

[Andy:] And this has to end. This has to end now. Because, in fact, we are worse off than the Chinese were 25 years ago. 25 years ago, the Chinese started from zero.We’re starting from the negatives because we’ve already been captured. We are already beholden to American tech

[Andy:] And so it needs to change. And the way that we change this, people in Brussels say, oh, we need to regulate.

Brussels’ answer to everything is a regulation. Well, you have the DMA now, and how well has that worked? I would say it’s been a complete failure. It hasn’t changed anything at all. So we need to approach it from a different angle.

[Andy:] People always said, oh, the problem with Europe is it’s a supply problem. We don’t have companies that can supply this tech that we need. But that’s a misconception. The problem is not supply. The problem is actually demand. You don’t have supply because you don’t have demand.

Because why? All the demand that you generate in Europe goes to American companies. You’re buying American stuff. So in my opinion, the answer is to adopt policies that require public procurement, which is again, the spending of taxpayer money to buy European. Why should our taxpayer money that today goes to government agencies, which then go out and buy technology, be used to subsidize American businesses? It doesn’t make any sense.

I think every single government contract in the EU and in Europe needs to go to a European company. That should just be law. And we should just do it because it’s good for the economy. It’s good for national security. And it’s in our national interest. And so I think that’s how we change the system. That’s how we fix it. And we need to have the buy European mindset today.

[Bruce:] Wow. I mean, I hear lobbying groups or citizen action groups starting to say something very similar. You know, we need to kickstart, if you like, a European industrial revolution for our own tech. It’s not like Europe lacks the talent. And it’s not like you need gigantic factories to press copies of spreadsheet software. You know, once it’s written, it’s infinitely reproducible. We have lots of brains here. I think you’re right. It’s just people naturally go and buy Chromebooks or Microsoft Windows in government, et cetera.

[Andy:] Yes. And there’s actually an industry group called Eurostack that has actually 200 companies in Europe that is focused on this putting together policy initiatives to bring about this change. But it’s the only way to do it. It’s, to be honest, how the Chinese did it. The Chinese simply created demand for their own companies by locking out American players.

] And while we cannot mandate what private companies do, the public sector, the governments, they’re spending taxpayer money. We can definitely mandate and demand where they spend their money. And I think for too long, European money and treasure has been subsidizing American businesses. And it’s time for us to believe in our own businesses and time to subsidize our own continent. It’s honestly very, very long past due.

[Bruce:] If you stand, I’m going to vote for you. Actually, I can’t because I’m not an EU citizen anymore. But Andy, I realize I’ve taken up nearly the whole hour. A couple more questions. What’s next then for Proton or what can you talk about publicly that’s next on the agenda for Proton?

[Andy:] Oh, you know, publicly is always a little bit tricky. I would say our model is very simple, right? We’re different from Google because Google is there to make advertisers happy. We don’t sell ads. We don’t have venture capital shareholders.

In fact, our main stakeholder is users. It’s the community. All of you out there that use our services, whoever you tell us that you want, actually we’re obligated to build it for you because you are our main stakeholder now.

[Andy:] The goal of the foundation is actually to serve the world, serve the community. So anything that enough people in the community ask for, we have to build. And you hear all the usual things, right? Now that we’ve launched our Proton Docs to replace Google Docs, people want Sheets. So probably have to do that as well, right? People say, oh, we need some more, we want secure chat services based in Europe. Okay, probably we have to do that as well, right?

Now there’s all this stuff going on with AI and people are pushing into AI. I think there’s some people that say AI is surveillance, but that’s like saying the web is surveillance, right? It’s true, but it’s not helpful, right? It doesn’t mean that the AI or the web is going to go away. So I do think in the privacy space, we need to figure out how we do AI in a privacy-first way.

And I think we recently pushed out a new feature that allows you to do albums on Proton Drive to have all your photo albums there, right? That was also something that users demanded quite a bit.

So our vision in the long run is really to build out the entire ecosystem. And that means everything that Google and Apple have, well, we in theory should do it as well. Because if you’re missing bits and pieces, it’s very hard for people to migrate over from Google’s ecosystem to a Proton ecosystem. So the mission is big. It’ll take us a long time. So please have some patience with this because it’ll probably be another 20, maybe 30 years before I do it. But I think it’s extremely important.

[Andy:] And we’re doing this also here in Europe, right? We have today 90% of our staff in Europe. And that’s because I believe sooner or later, there’s going to have to be a European tech giant. And this is, I think, the opportunity. You know, because at the end of the day, who we’re fighting for is actually European values. And you will not be able to defend your values if you don’t have the sovereignty of your own technology, right?

So European values will only exist 100 years from now if we have the tech ourselves to sustain and support that. And this is ultimately what Proton is trying to do.

[Bruce:] Wow, I mean, this is why Vivaldi, we’re very excited to be partnered with Proton because similar value proposition. We have no external investors to force us to pivot, or to gouge more money. If our users want something, we’ll do our best to make it happen.

We can’t always make stuff happen as fast as people want because lots of users mean lots of competing requests. But, yeah, we’re there to keep the internet free and open, and not monetize people while doing it.

[Andy:] Yeah, and I think I’m quite excited that we were able to work together because I think European companies, there aren’t that many of us that are trying to do things the right way. and we’re all quite small, at least compared today to our American Chinese counterparts. We’re going to get bigger over time. So maybe this will not be two or 10 years, but today we’re all quite small. And the only way to make more progress is actually by working together.

And I think that’s also the strength of Europe. So when it comes to Eurostack, it cannot be German industrial policy or French industrial policy. It has to be all-Europe industrial policy. Because on our own, we’re too small. But together as a group, together as all the 20 plus countries, actually close to 30 countries now in the EU, that is where our power lies. Because that is combined, we’re an economy with more people, more engineers, highly educated, and actually also more spending power as well. So we have the ingredients to actually be the global leaders. Now we just need the political will to actually do it.

[Bruce:] Well, I hope we will. And I hope before I retire, that you will come and join me on my Vivaldi super yacht when we celebrate our billionth user. So it’s an open invitation for that.

My last question, Andy, because time is running out. I want to go back to particle physics, which fascinates me, as I say, even though… One of the best books I ever read is called The First Three Minutes by Steven Weinberg. So as far as I can tell, the heaviest hadron found to date at the Large Hadron Collider rejoices in the name Double Hidden Charm Tetraquark. Can we expect Proton to rebrand as “Double Hidden Charm Tetraquark”?

[Andy:] Well, you know, in the tech industry, there’s a famous three-syllable rule, right? If the name of your company is more than three syllables, it’s probably going to fail. So on that basis, I’m going to have to refuse this proposal.

[Bruce:] Excellent. So once again, proof of no decay of the Proton. I like it. Andy Yen, thank you so much for your time. And it’s really invigorating to hear other people expressing the same hopes and visions for European tech as I share personally, and Vivaldi shares organizationally.

So thank you very much for being our guest. And let’s meet up in 10 years’ time and work out how well we’ve done.

[Andy:] Great. Thanks for having me. And it was a pleasure to be here. And we’ll stay in touch.

[Bruce:] Thank you. And thank you very much, listeners and viewers, for being with us. See you next time.

Show notes

- Proton on was-Twitter

- DH Lawrence’s Relativity poem

- Simon Migliano, Top10VPN

- Proton Foundation

- Swiss ordinance changes

- Proton threatens to quit Switzerland over new surveillance law

- Gail Slater, The Woman Leading the Surging MAGA Antitrust Movement

- A judge just blew up Apple’s control of the App Store

- EuroStack

- The First Three Minutes

- Double Hidden Charm Tetraquark